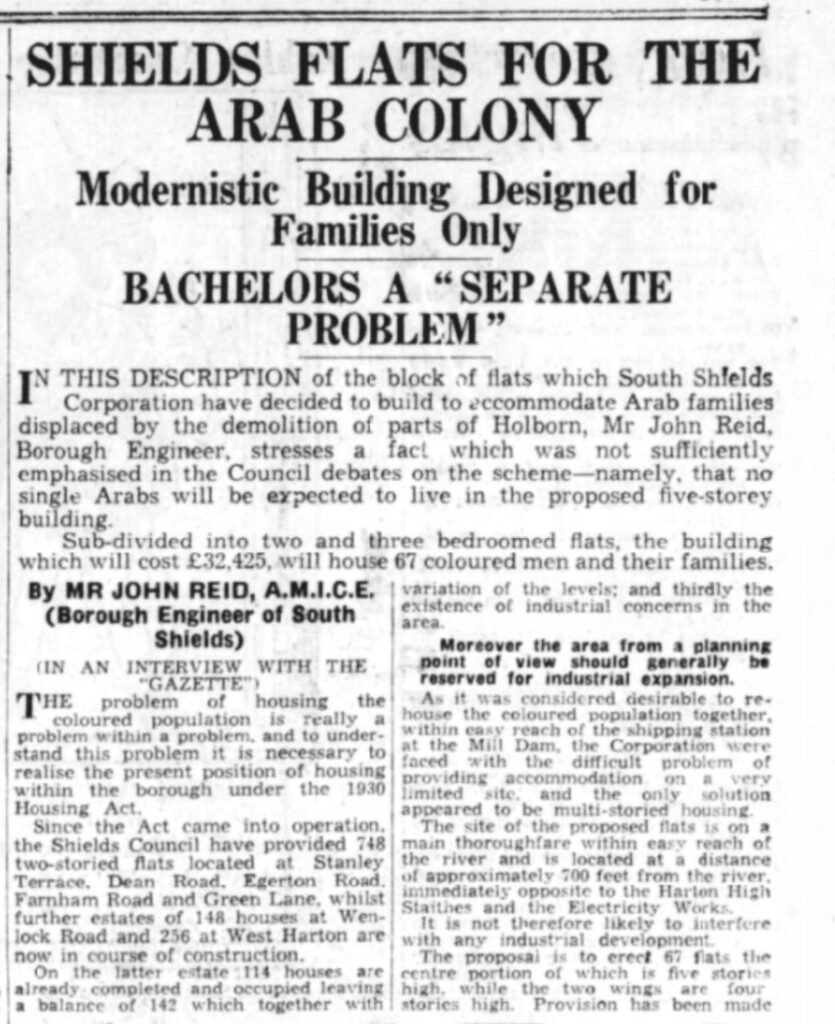

The 1930s Demolition of Holborn

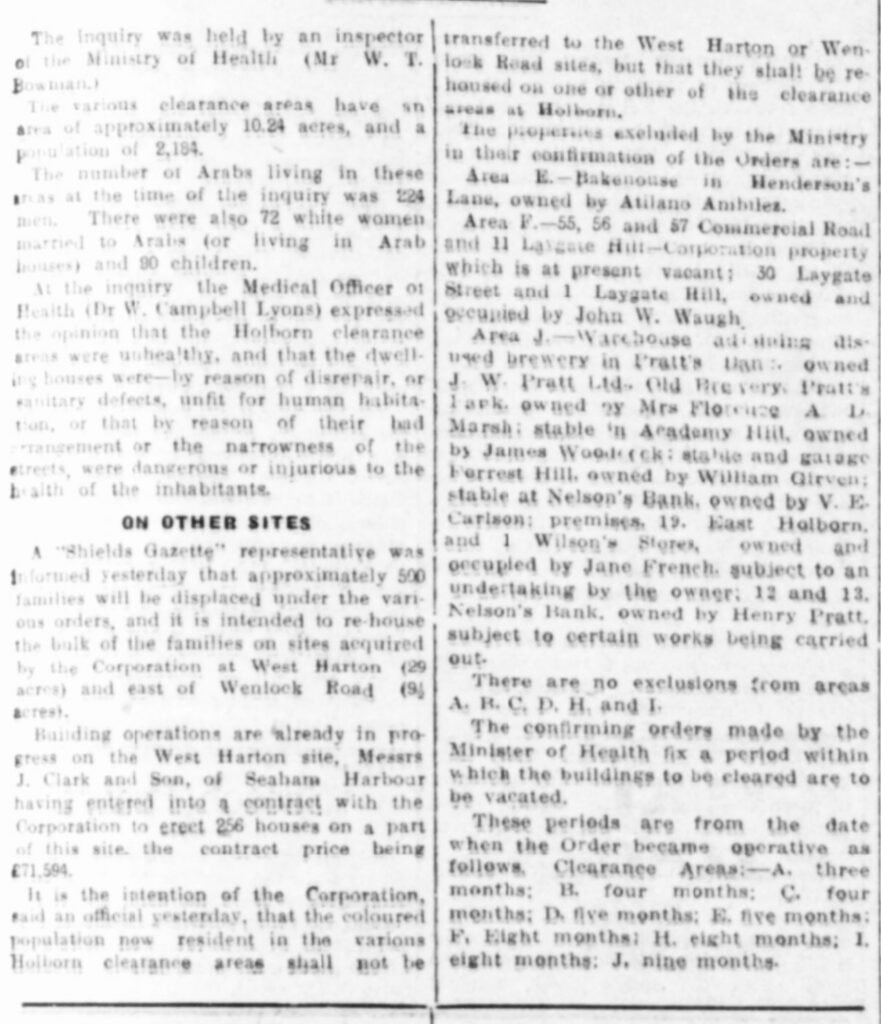

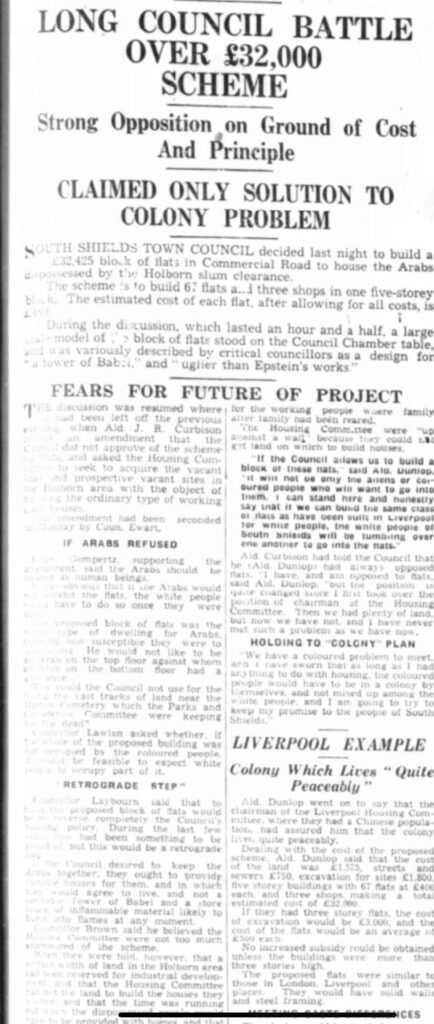

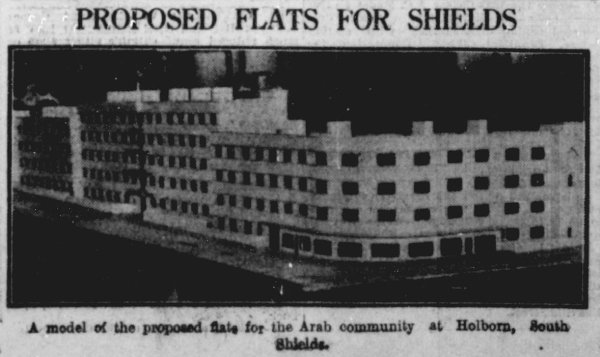

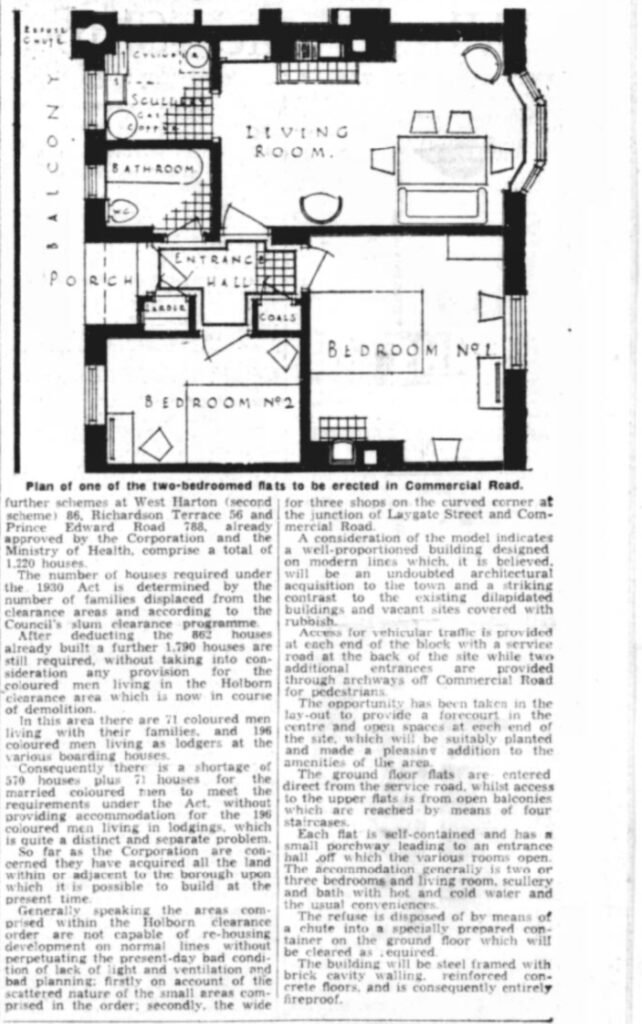

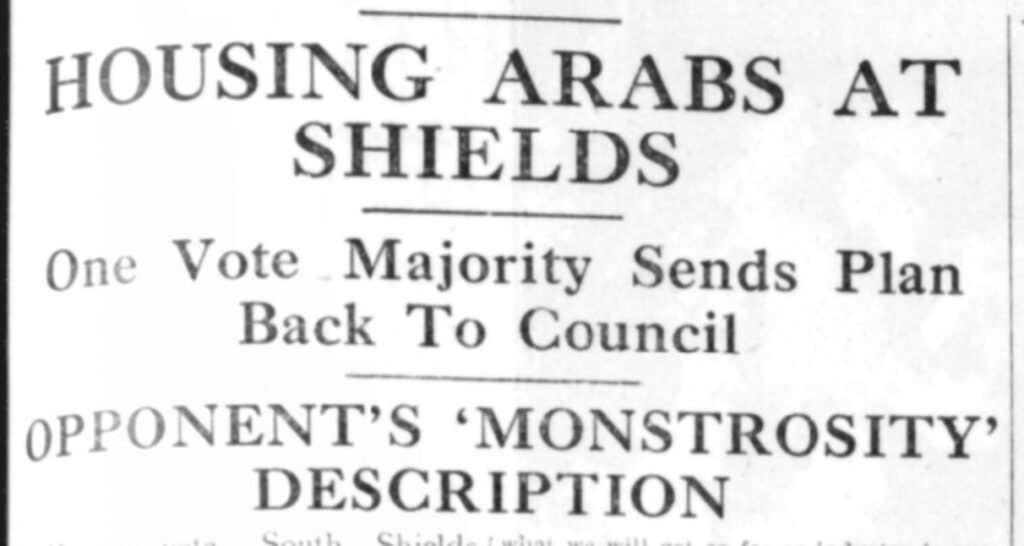

The 1930’s demolition of Holborn posed new questions for Council officials in South Shields such as where to re-house the resident Arab population. The original suggestion was the building of four/five storied flats on Commercial Road itself to house the community together.

(c) The Shields Gazette 08/03/1934

“There is a danger,” the author writes, “of the Arabs penetrating, as they have already done in isolated cases, into good-class residential areas in South Shields.” The writer continues, “Public opinion is inclined to the belief that they should be kept together.”1

(c) The Shields Gazette 12/07/1934

The demolition of Holborn in what were described as ‘slum clearances’ 1939 – West Holborn (c) South Tyneside Libraries

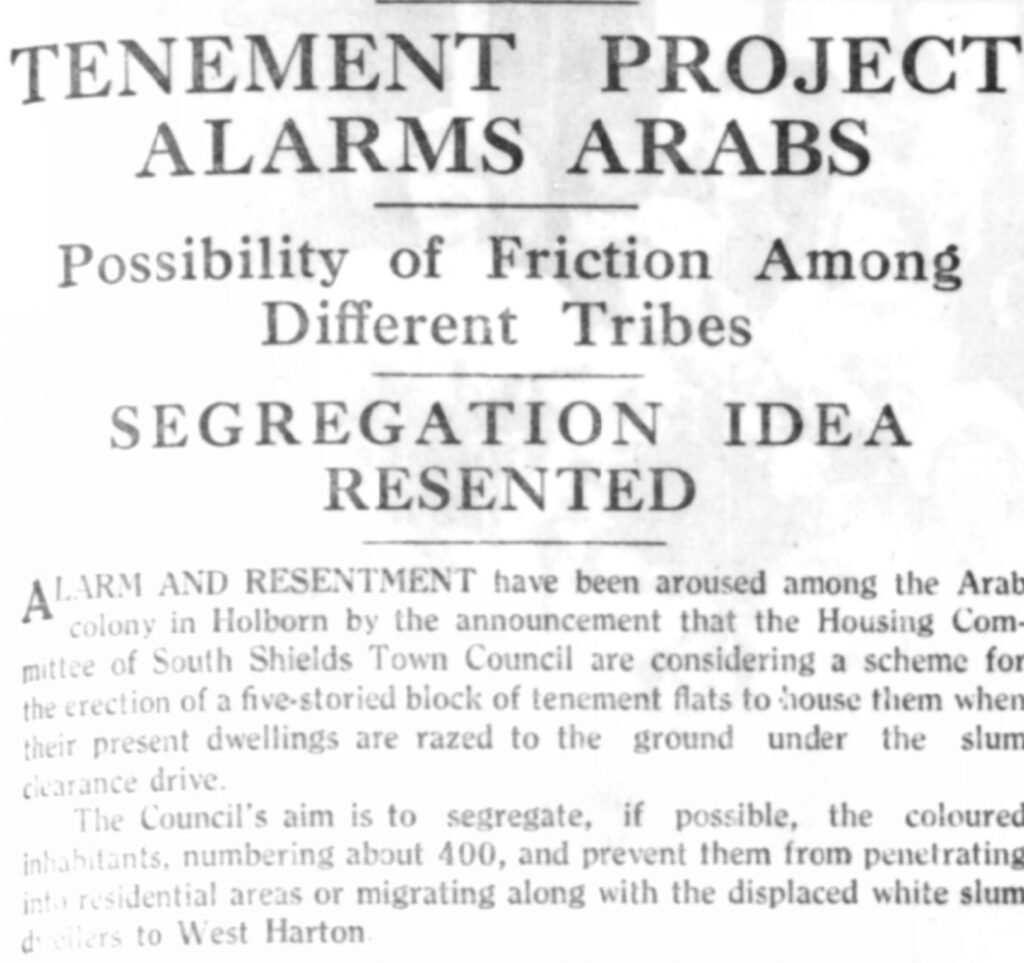

The proposal was met with alarm by the South Shields Arab Community.

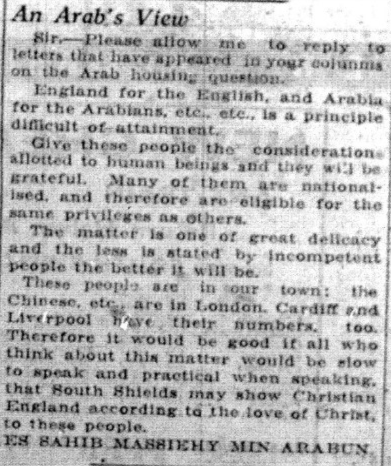

Many boarding-house masters such as Said Marbrouk wrote into the Gazette concerned about how they would make their living should their boarding houses be demolished. The future of their boarders and the assurance of having their debts repaid was also at risk under the scheme. One Arab went a step further in his correspondence with the Gazette:

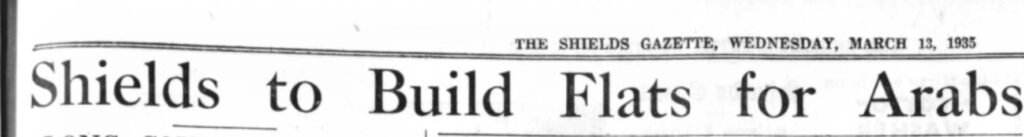

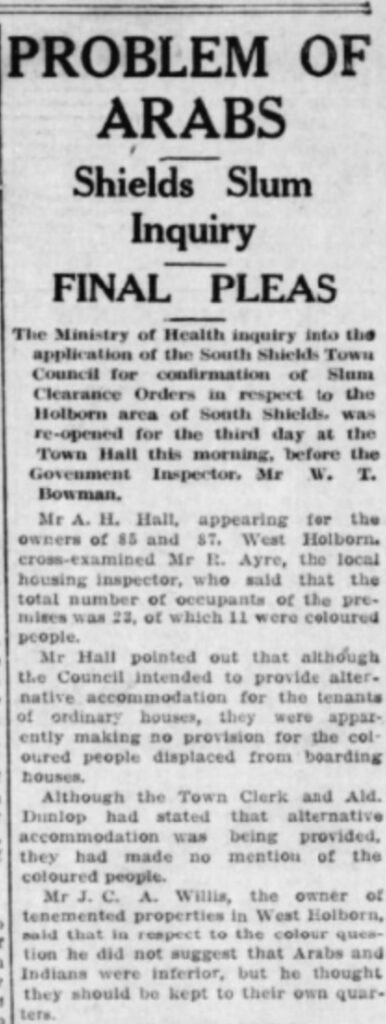

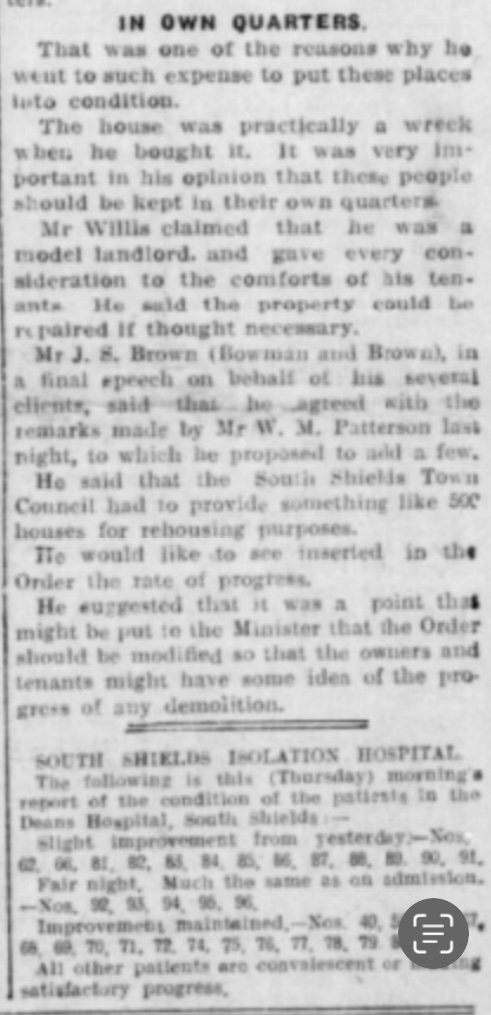

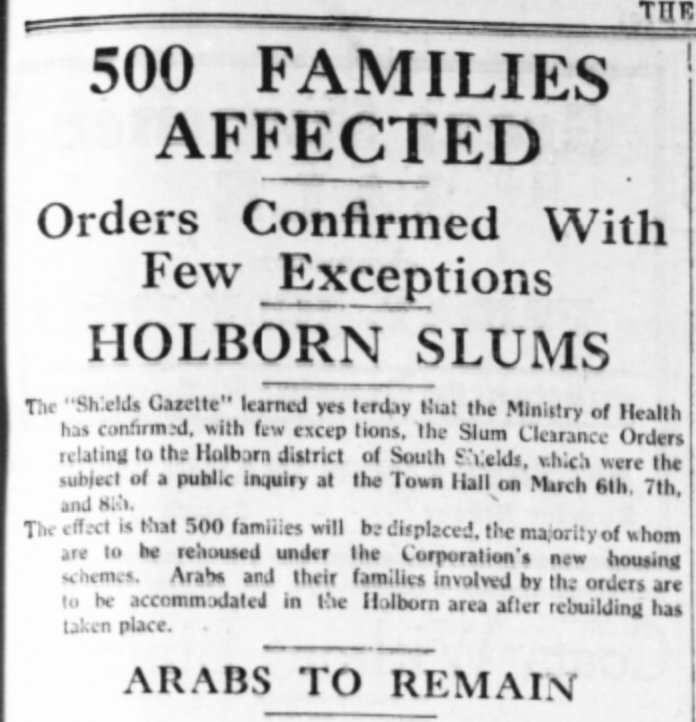

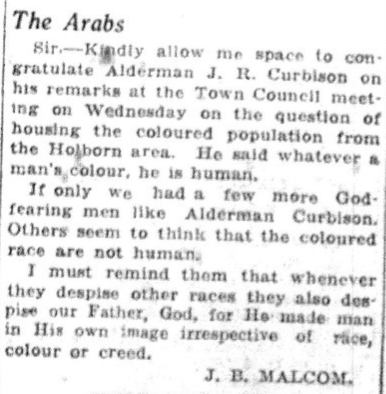

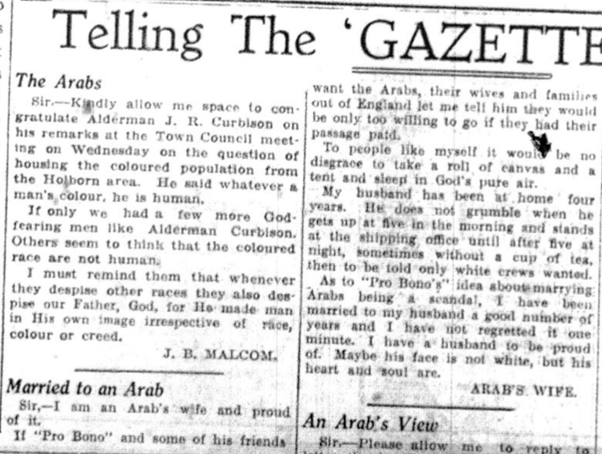

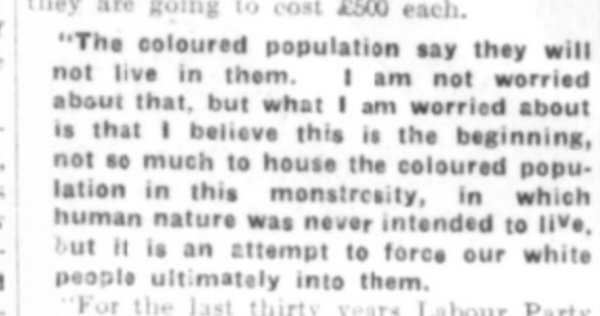

The issue was one of much debate and discussion both inside the council chamber and out. Some extracts of this discussion and proposals put forward during 1935 are shown below:

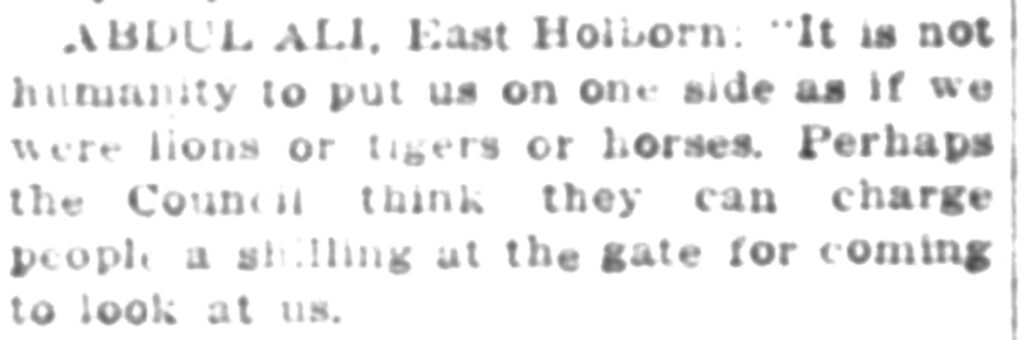

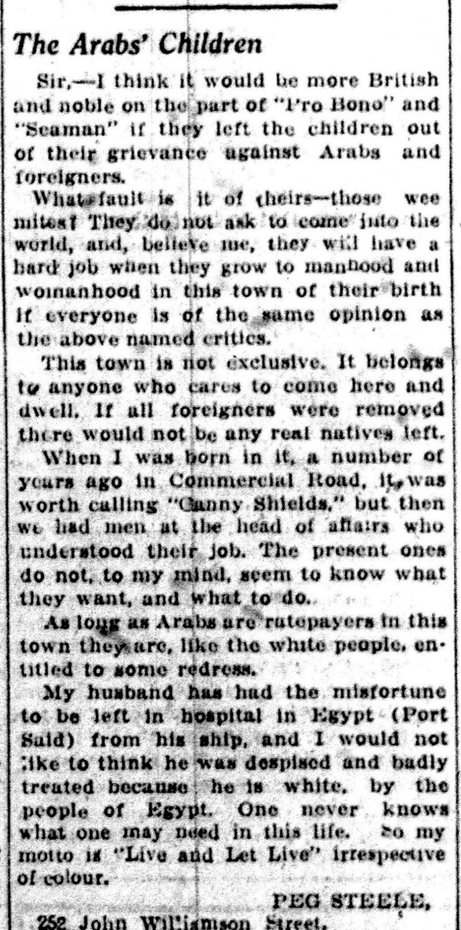

Reaction of the local community: “Be grateful”

(c) The Shields Gazette 02/02/1935

A defence

(c) Shields Gazette 13/03/1935

(c) Shields Gazette 08/03/1935

(c) The Shields Gazette 16/03/35

“Yemeni residents wrote to the Shields Gazette in response. “During the war I was in Ruhleben prison camp in Germany. I know what a camp is like,” wrote Salem Abuzed, a boarding house manager. “England is a free country and they cannot do things like this to us.”3

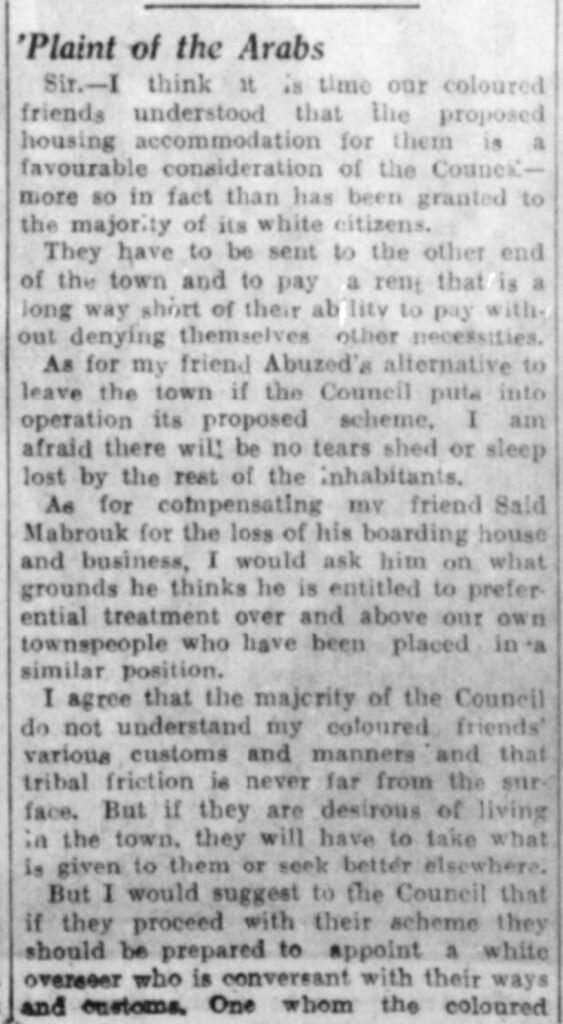

Opinion divided

(c) The Shields Gazette 20/02/1935

(c) The Shields Gazette 16/10/1937

Solution to the ‘problem’.

“In March 1937 Dr Lyons, the Medical Officer of Health for South Shields, (…) urged (…) that the housing of coloured men and their families be given further consideration. (…) He put forward the suggestion that part of the new Commercial Road estates might be set aside for use of the coloured community. This suggestion was followed up by a deputation representing women of the Arab community.”8

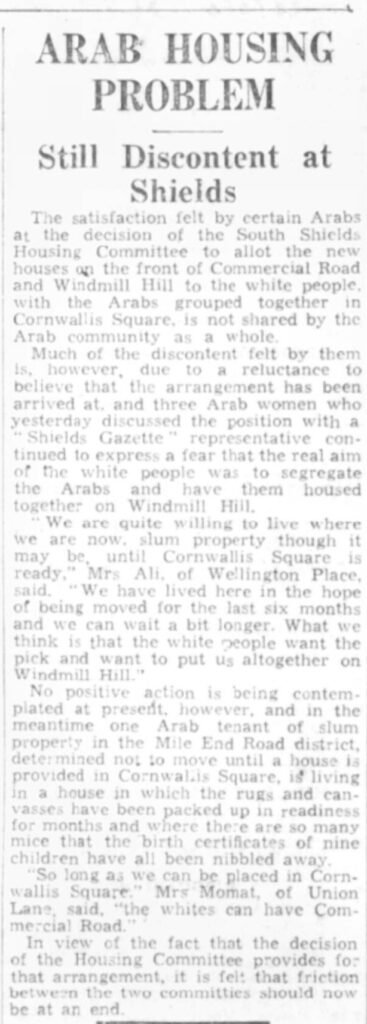

“At the next meeting of the Housing Committee on 14 October, it recommended to the Town Council that white residents should be allocated new houses on the front of Commercial Road and Windmill Hill and that Arab families be grouped together in Cornwallis Square at the rear.”9

This proposal worked well for all parties. Cornwallis Square was close to the Mill Dam and it was close to Holy Trinity Church where the community had proposed to build their future mosque. It kept the Arabs segregated from the wider South Shields community however, there were not enough properties to rehouse everyone and the demolition of Holborn began before the re-housing scheme was finalised. Shop owners and boarding house keepers were not factored into these plans and many lost their livelihood. These various factors meant that in reality, some Arabs did re-house outside of the ‘desired’ area. In fact, many Arab and white families did live alongside each other in the Laygate area despite the council refusing to rent to Arabs any houses except Cornwallis Square. In theory, there was no legislation that prevented Arabs renting or buying property across the town however, the prejudice they faced upon doing so made life very difficult.

- Lawless, R.I. (1995). From Taʻizz to Tyneside. p. ↩︎

- (c) The Shields Gazette https://www.shieldsgazette.com ↩︎

- https://delacortereview.org/2019/02/17/true-north/?utm_source=chatgpt.com ↩︎

- (c) The Shields Gazette https://www.shieldsgazette.com ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Lawless, R.I. (1995). From Taʻizz to Tyneside. p. 203 ↩︎

- Ibid., 204 ↩︎