British Aliens

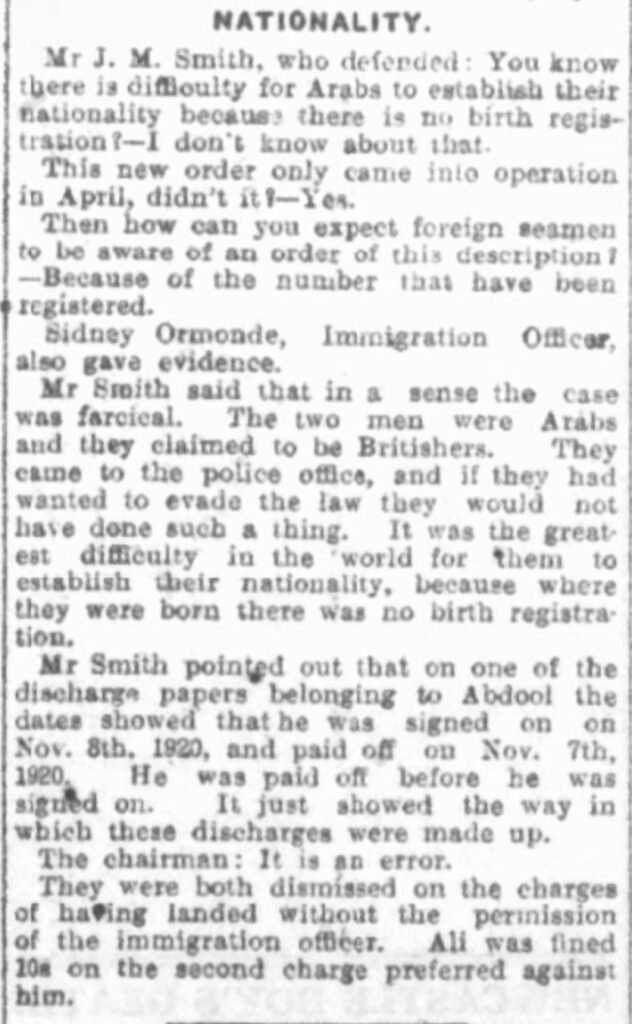

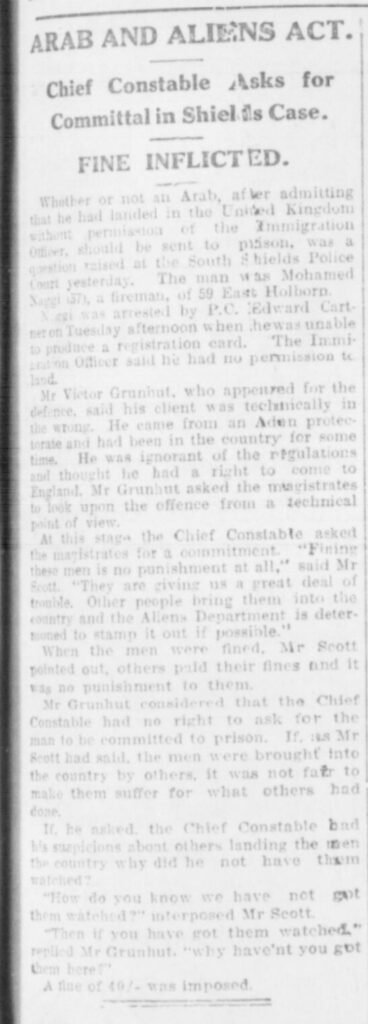

Only Yemenis born in Aden were classed as British subjects and eligible for British protectorate status and nationality. Few could prove it as birth certificates were not routinely issued. Lawless states: “when questioned by immigration officials almost all the Arab seamen who arrived in South Shields (…) invariably claimed that they were born in Aden and were therefore British subjects.” 1

The attitude towards the nationality of Arab seamen changed depending on the need of Britain for their labour. During the First World War, officials in Aden turned a blind eye to the legality of where Arabs were born, whether that was inside or outside the boundaries of the protectorate. In South Shields also, this era was relaxed in terms of immigration status. “Their status as British subjects does not appear to have been challenged locally until March 1917 when three boarding housekeepers, Ali said, Mohammed Mikayl and Abdul Rahman Zaid were charged with failure to register as aliens.” by choosing to prosecute the three main boarding housekeepers of that era, it is clear that this was an effort to make an example of these men for the benefit of the wider Arab community. The court case so witness testament from the men’s solicitor, Mr Ruddock, William Albert Stephenson-an official of the shipping Federation and Joseph Harrison Surtees- manager of cooks tourist agency who testified that there were no restrictions placed on these Arab semen and that there had been no difficulty in getting passports for the board as lodging with these men.

Lawless states in his prominent book ‘From Taiz to Tyneside’ that “the Board of Trade suggested to the Home Office that the claims of Arab seamen to British nationality should not be challenged”2

“From the outset it would appear that Arab seamen engaged at Aden were hardly ever British subjects or even permanent residents of Aden.”3

Following the outbreak of the First World War, the British authorities in Aden advised that Arabs from parts of Arabia outside British jurisdiction engaged as seamen at Aden should be treated as British Protected Persons to facilitate their departure from European ports such as Marseille” 4

The incentive to embark

wages before and during the war on vessels employed in foreign trade

1914. – £5.10s

1916 – £9

1918 – £14.10

(c) From Taiz to Tyneside pg 115

control and regulation

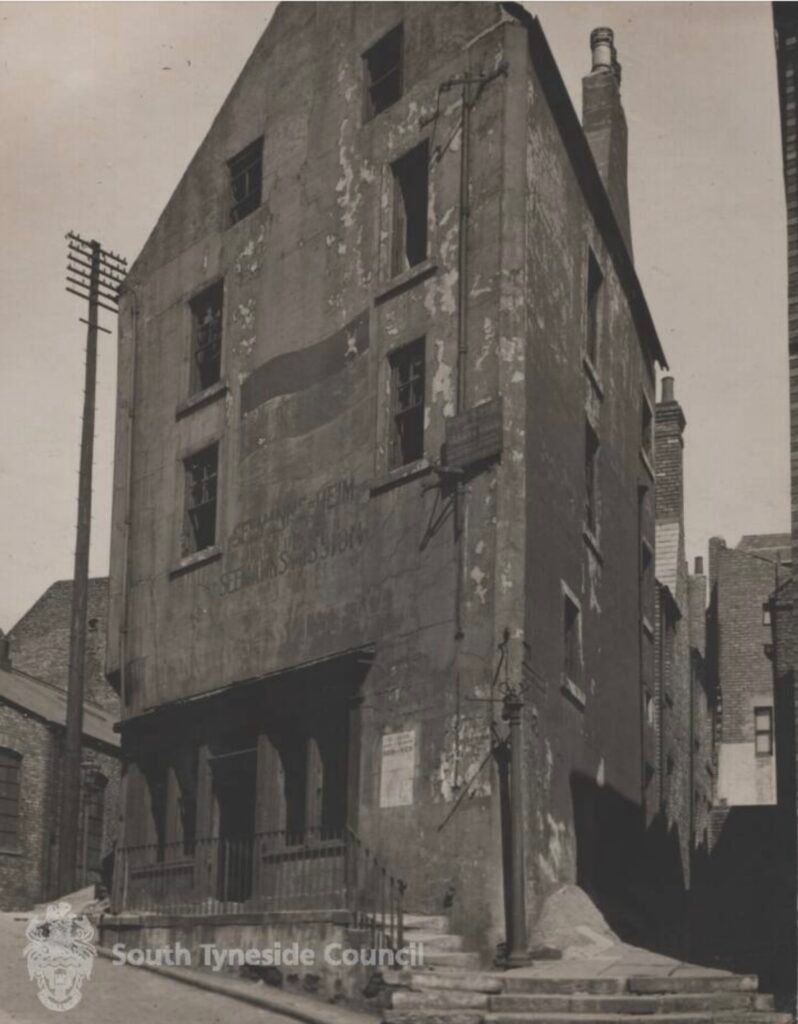

(c) South Tyneside Libraries – The German Seamen’s Mission 1910

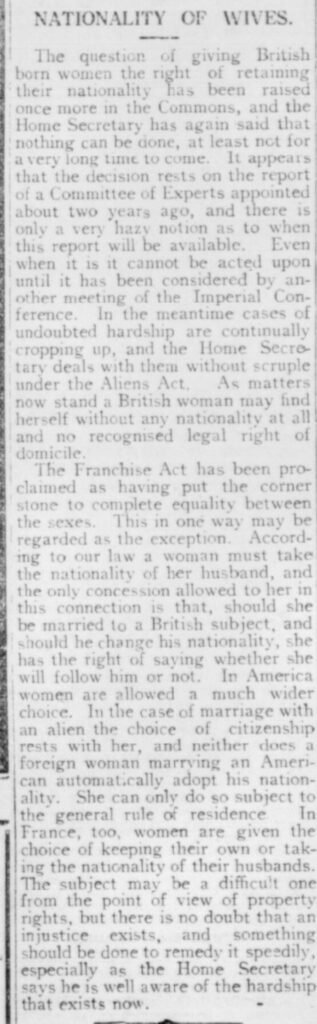

British women who had married these men were also classed as ‘aliens’, as per the 1914 Nationality Act (c) Shields Gazette 05/07/1928

Under the 1914 nationality act, which was not repealed until 1948 mean that a British woman who married a ‘foreign’ man, such as an Arab who wasn’t considered a British subject – automatically lost her British status unless this would make her stateless. In this scenario, children took the nationality of their fathers. A British woman who married a British Protected Person entered a legally ambiguous and often disadvantaged status under British nationality law of the time. They did usually retain their British nationality because a British Protected Person was not a foreign national. Their children being born in Britain attained British nationality by merit of their birth in Britain, through ‘right of the soil’.

pressure mounts

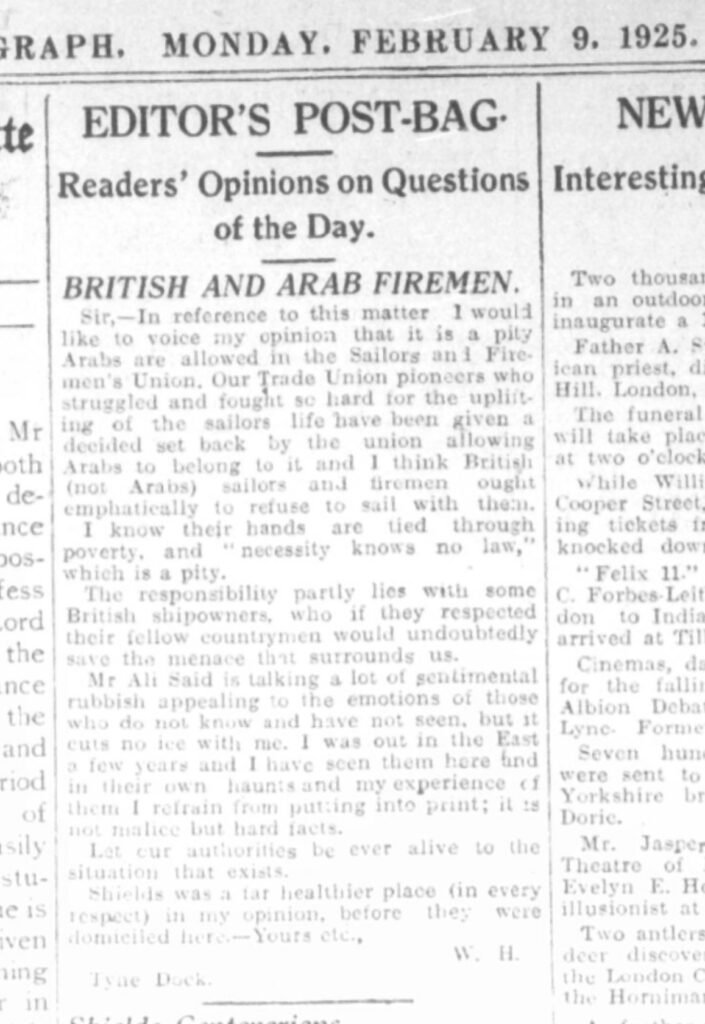

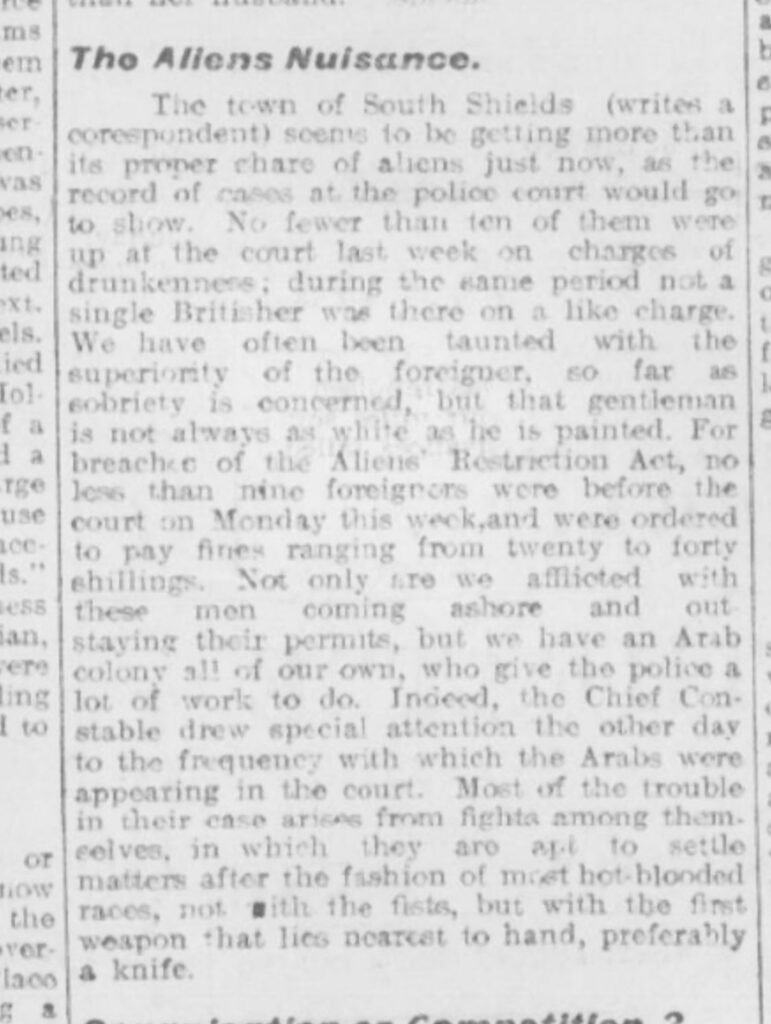

The years following the first world war however, were desperate and deprived. Many white British semen returned from the Royal Navy to find that the Arabs in South Shields were competing against them and gaining employment whilst they were unemployed. The resentment this caused was a huge source of contention which simmered for years occasionally exploding in a violent clashes where people were hurt, businesses targeted and lives lost.

Pressure grew on the authorities from the wider public to stop Arabs from taking jobs that were seen as the right of the white man. It became a part of the local and national political agenda. ‘The National Sailor and Fireman’s Union’ later known as ‘The National Union of Seamen’ were consistent and vitriolic in the continuous character assassinations of the Yemeni community in their own news publications. They lobbied The Board of Trade and the Shipping Federation fiercely to adopt preventative measures to stop more Arabs from coming to the country and to prevent them from work.

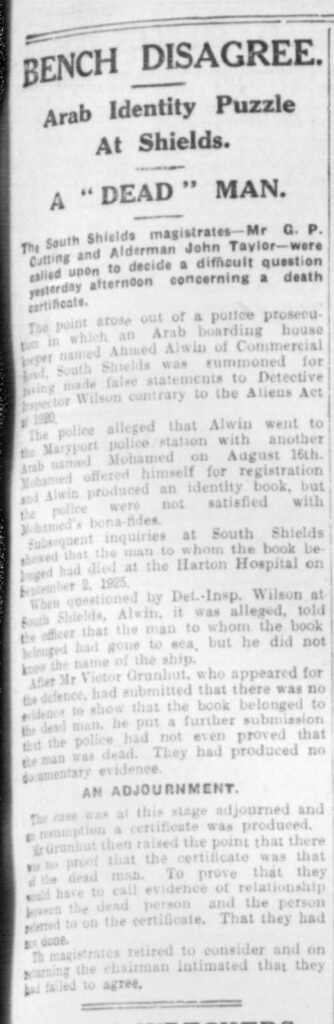

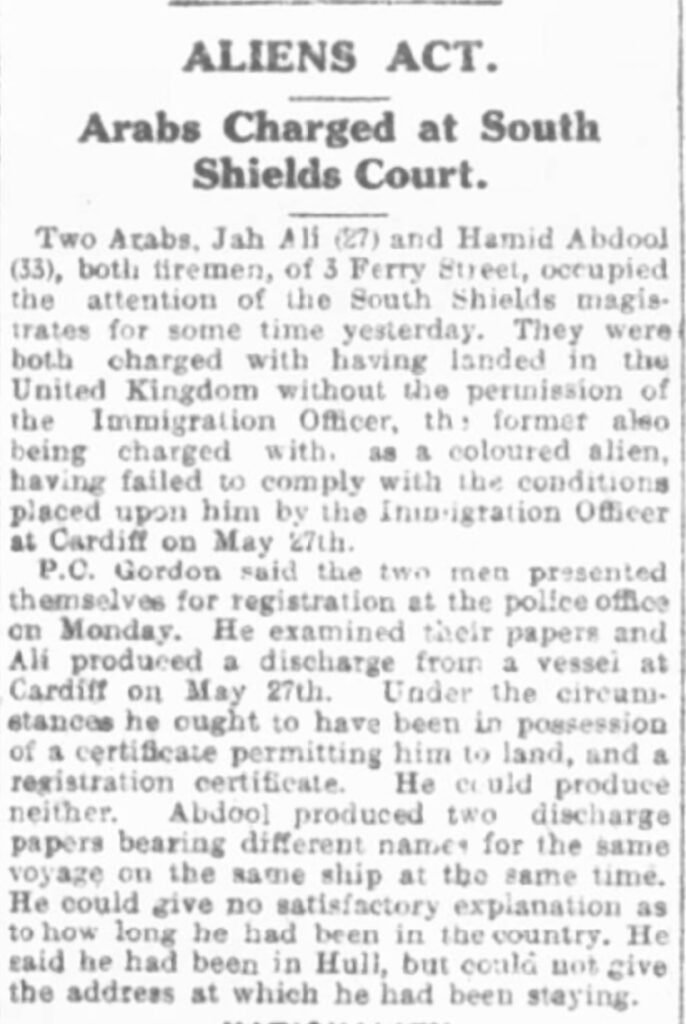

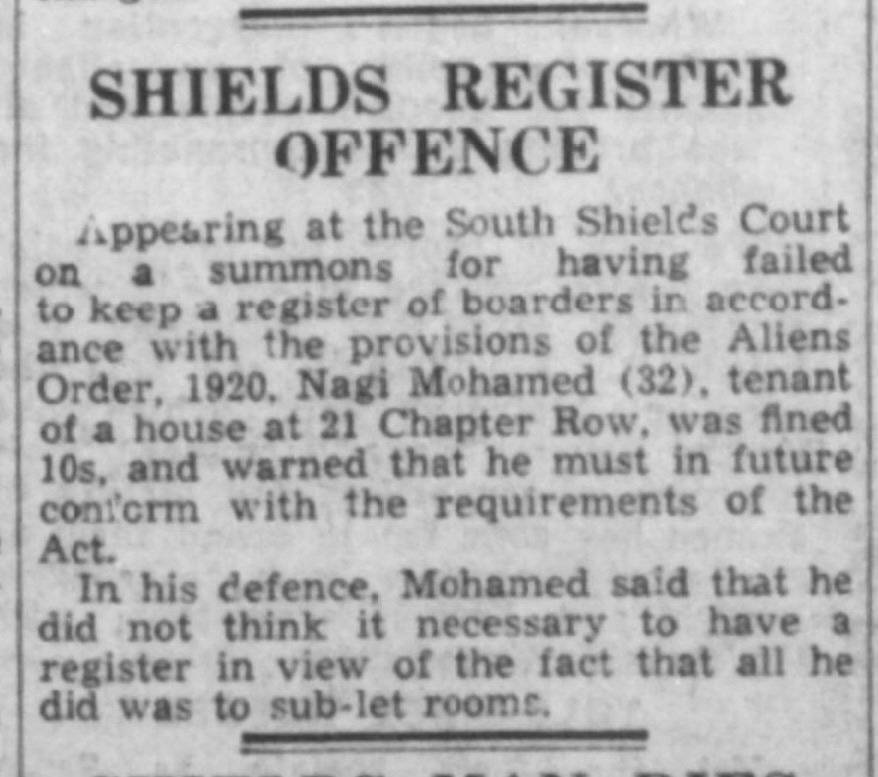

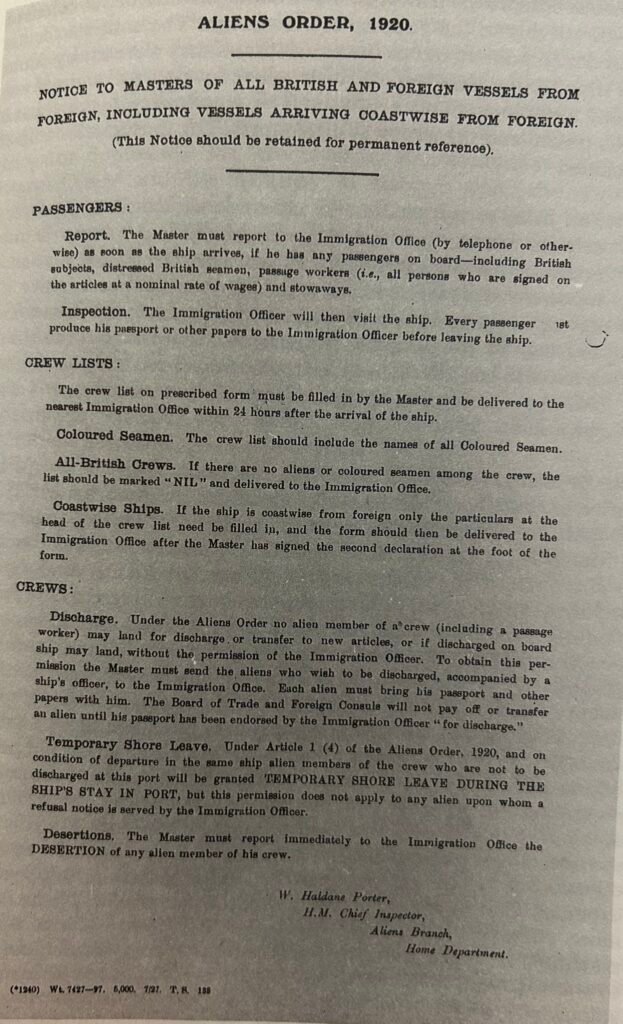

in 1920, The Aliens Order was implemented with the direct aim of preventing Arab seamen from landing on British soil unless they could prove that they were either a British subject, living in Britain, or had signed on for a round trip. This legislation was problematic in its enforcement primarily because implementing it was rolled out progressively meaning in its early stages, and an Arab could simply land in a non-participatory dock. Whilst restrictions tightened, it is notable that Aden was still a British Protectorate and under the flag of the Union Jack.

The Aliens Order 1920

Page 101- From Taiz to Tyneside, originally PRO HO 45/14299 The National Archives6

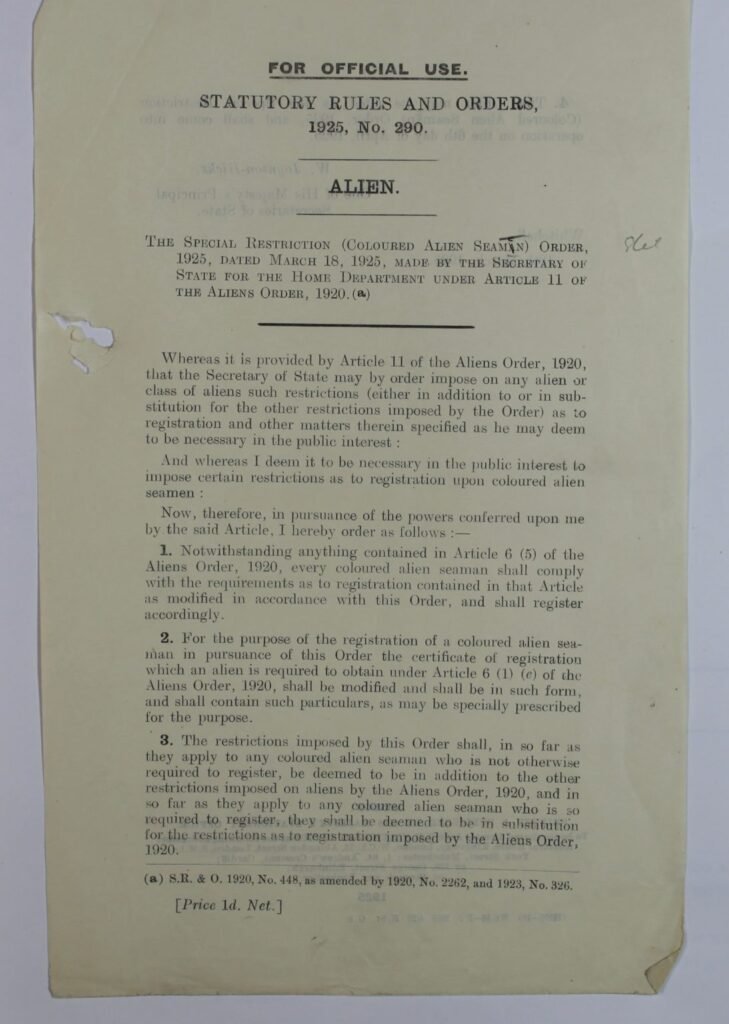

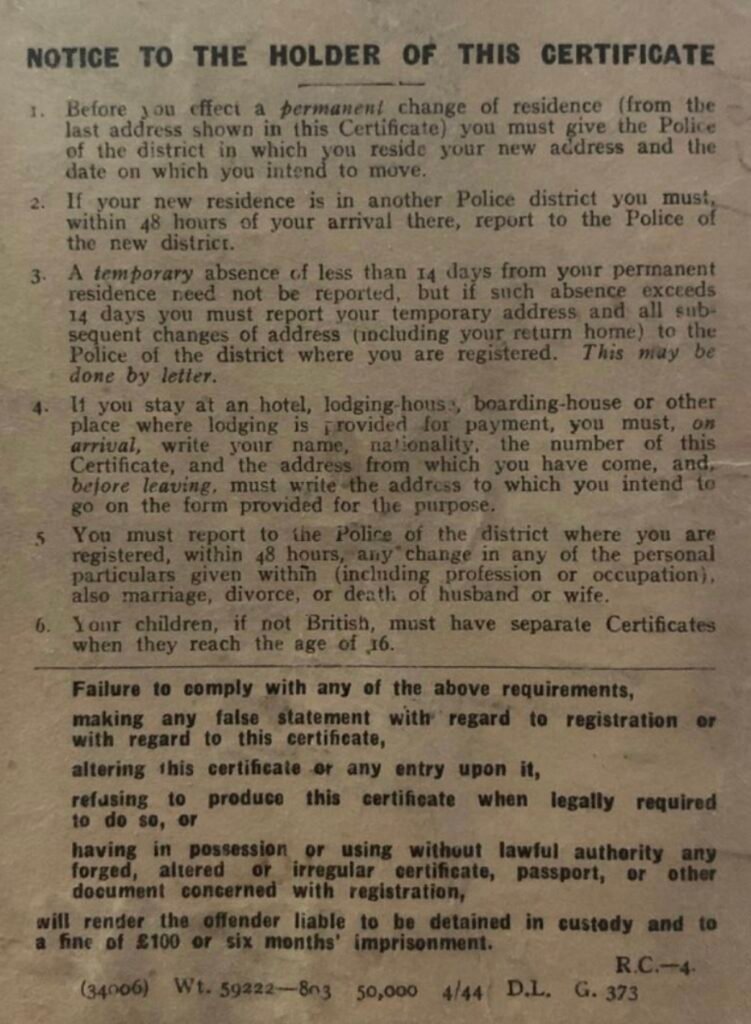

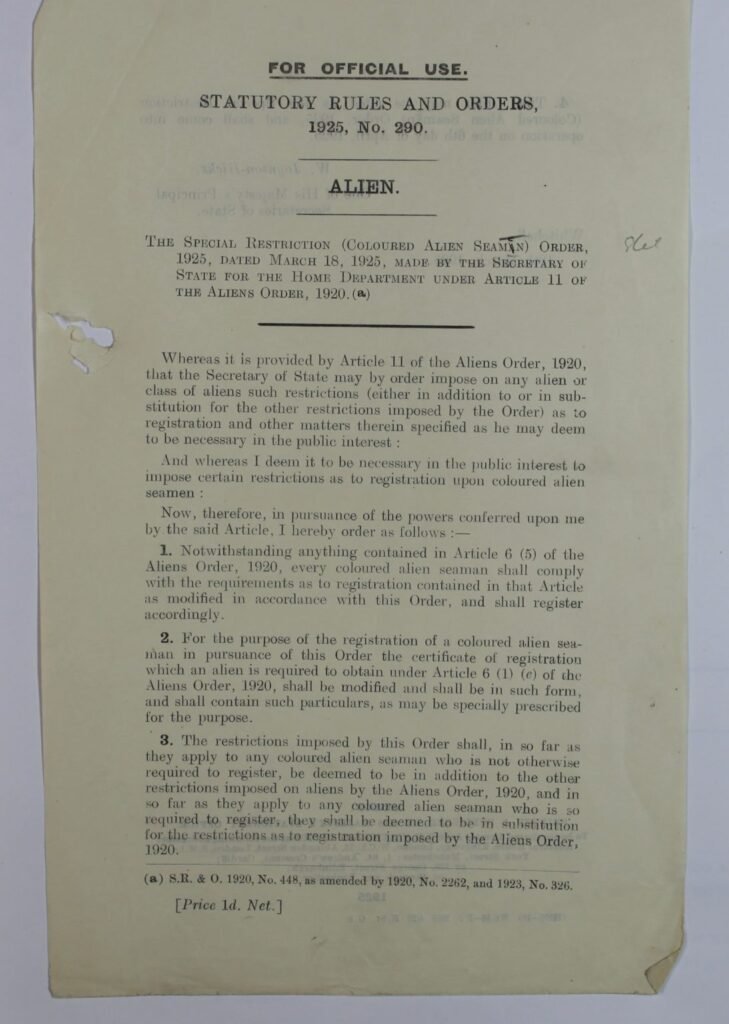

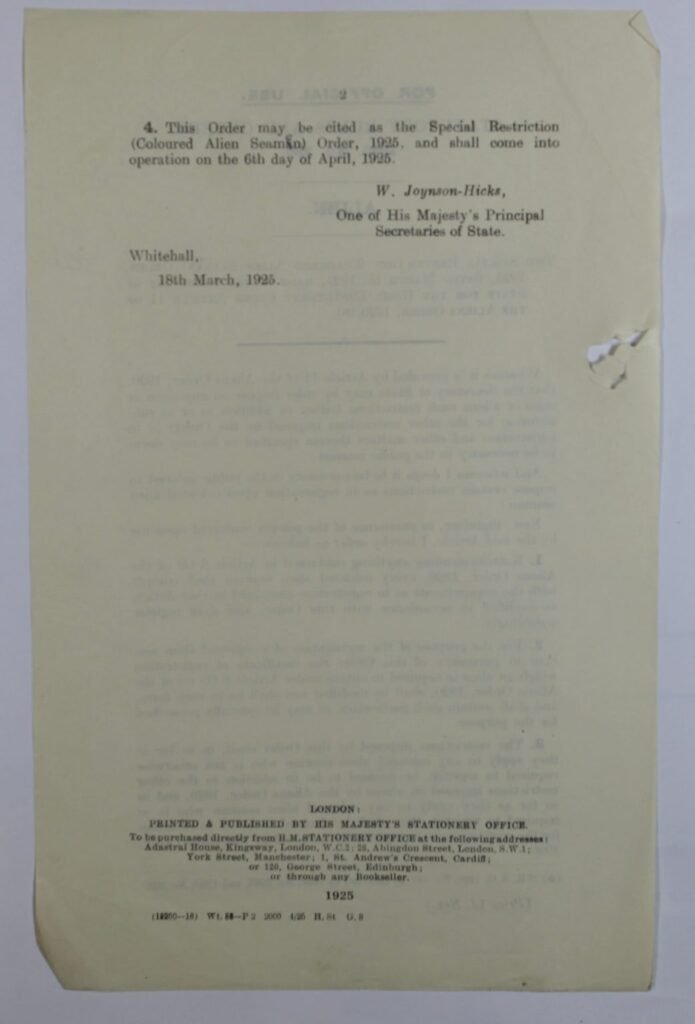

in 1925 under article 11 of the aliens order 1920, the special restrictions order was implemented. This required all colours to register and therefore be regulated and under police control. Upon implementation, Arabs residing in South Shields would have had six weeks to attend the local police station and sign up to receive a registration certificate. This registration certificate would prove to be essential for proving eligibility to be in the UK. These measures and restrictions form part of the earliest immigration laws in the United Kingdom and form the foundation of present immigration laws which in their historical context, were designed to control immigration and trade at the same time. Going forward, there was little way back for those who hadn’t registered in this 6 week period.

1925 Order. Catalogue ref: HO45/11897/332087/98 (via The National Archives)7

Brit or Alien? The Press Speculate

(c) The Shields Gazette 05/07/1928

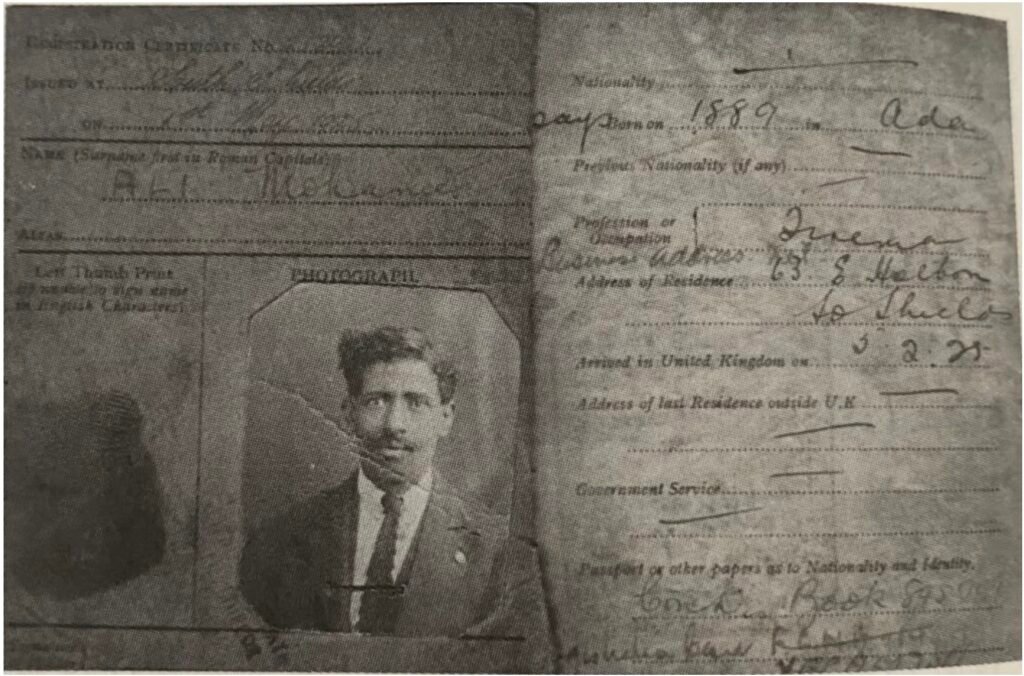

An example of a registration certificate:

Mohammed Ali (Sharkey)’s certificate of registration. (c) Leyla Al-Sayadi

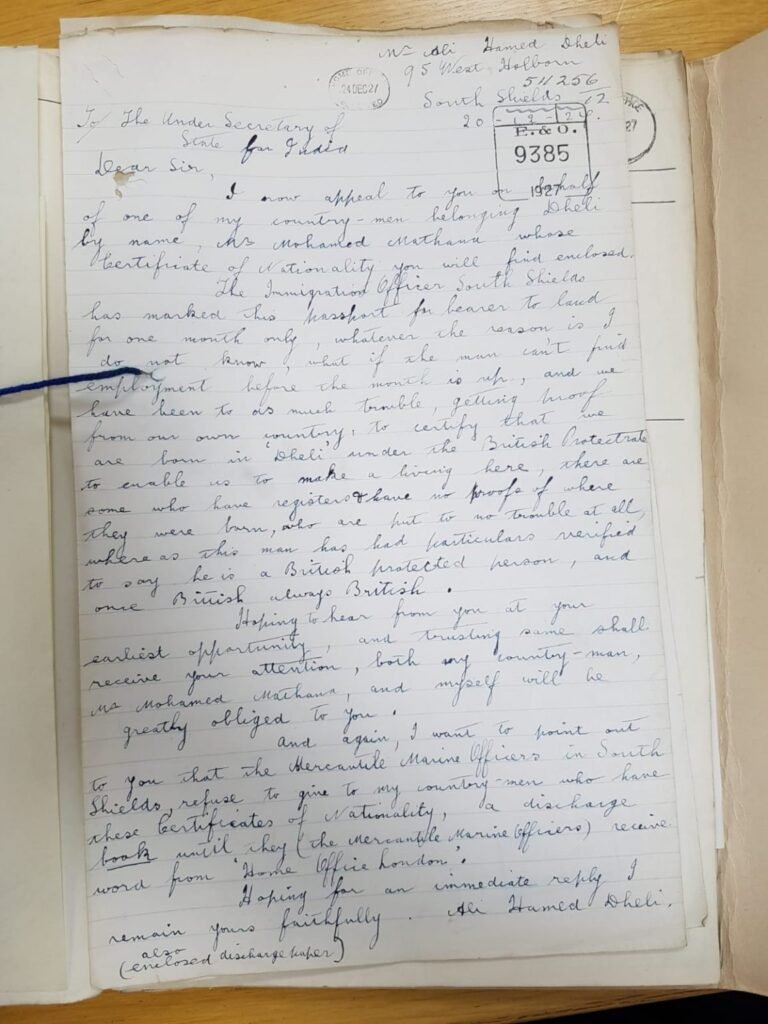

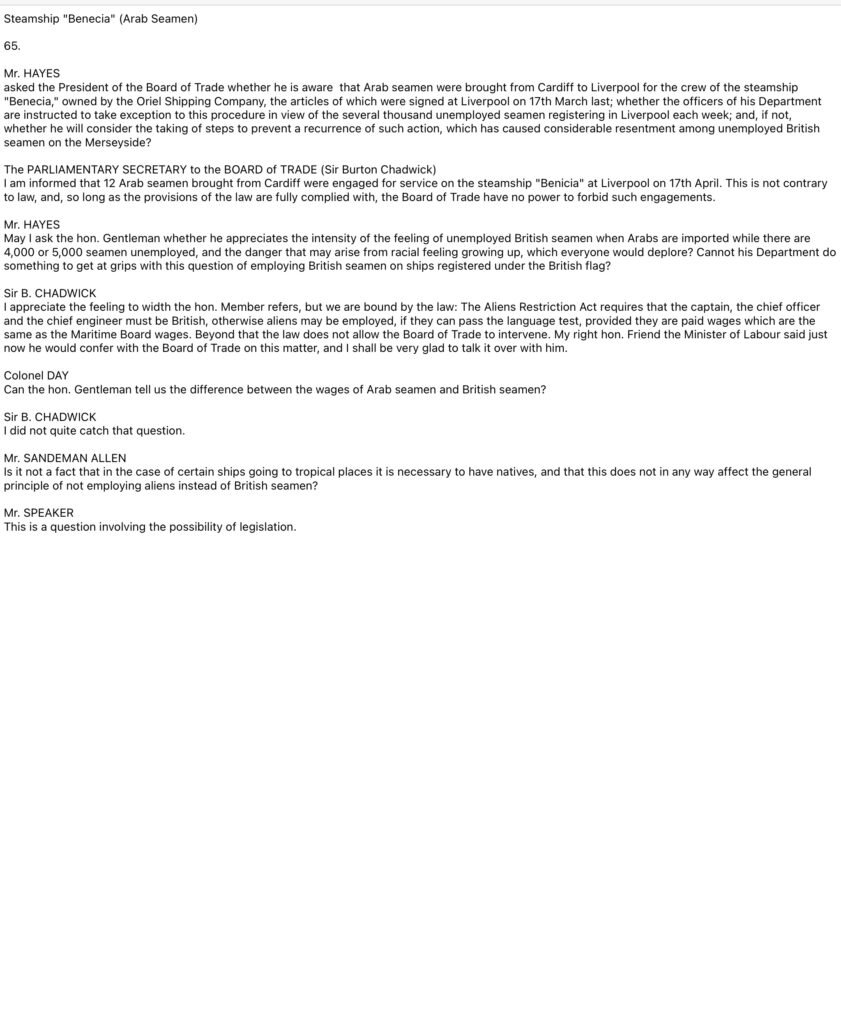

Letter to the Under Secretary of State for India

The tightening of registration and nationality procedures were making the lives of the Arab community more difficult. Ali Ahmed Dheli wrote a letter dated dated 20 December 1927 to the under Secretary of State for India asking for assistance for a man whose status was in dispute. Transcript provided below.

‘The Immigration Officer South Shields has marked his passport for bearer to land for one month only, whatever the reason is I do not know, what if the man can’t find employment before the month is up, and we have been to as much trouble, getting proof from our own country, to certify that we are born in ‘Dheli’ under the British Protectorate to enable us to make a living here, there are some who have registers and have no proofs of where they were born, who are put to no trouble at all, where as this man has had particulars verified to say he is a British protected person, and once British always British.’Transcript of letter. Catalogue ref: HO 45/13056,

Catalogue ref: HO 45/13056(via The National Archives)13

(c) Shields Gazette 04/02/1925

(c) The Shields Gazette 29/08/1917

(c) Shields Gazette 22/10/1930

“much of the discussion sent out on the question of the nationality of Arab semen. Viscount Wolmer for the board of trade, felt that it was important to recognise that they were three categories of Arab semen: those who had passports proving that they were British subject; those who had married English women and had settled down in Britain; and the class of purely alien Arabs who were trying to come into the country.

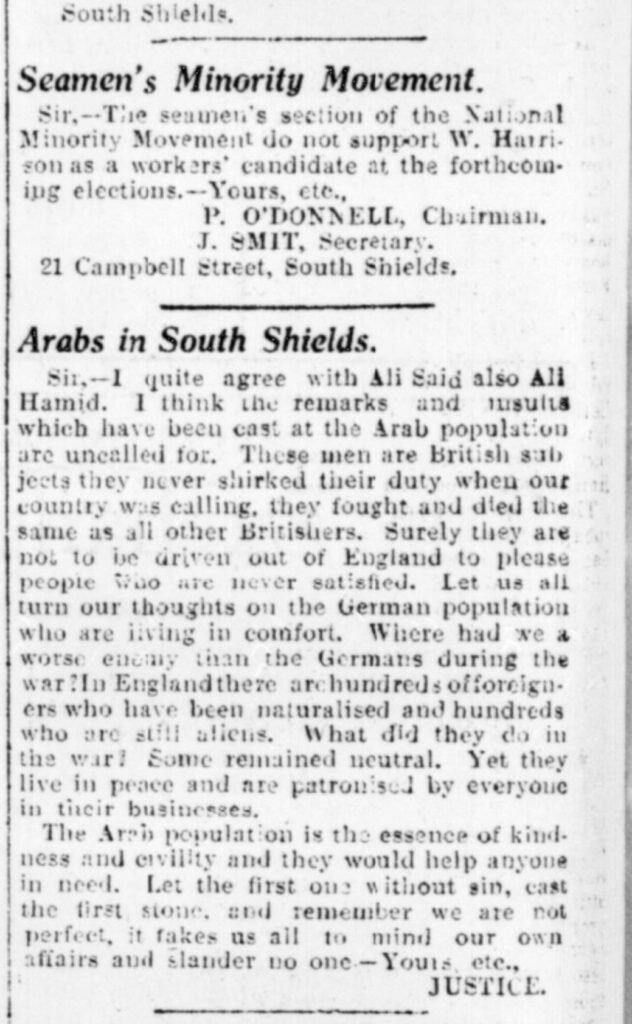

Naturalised subjects

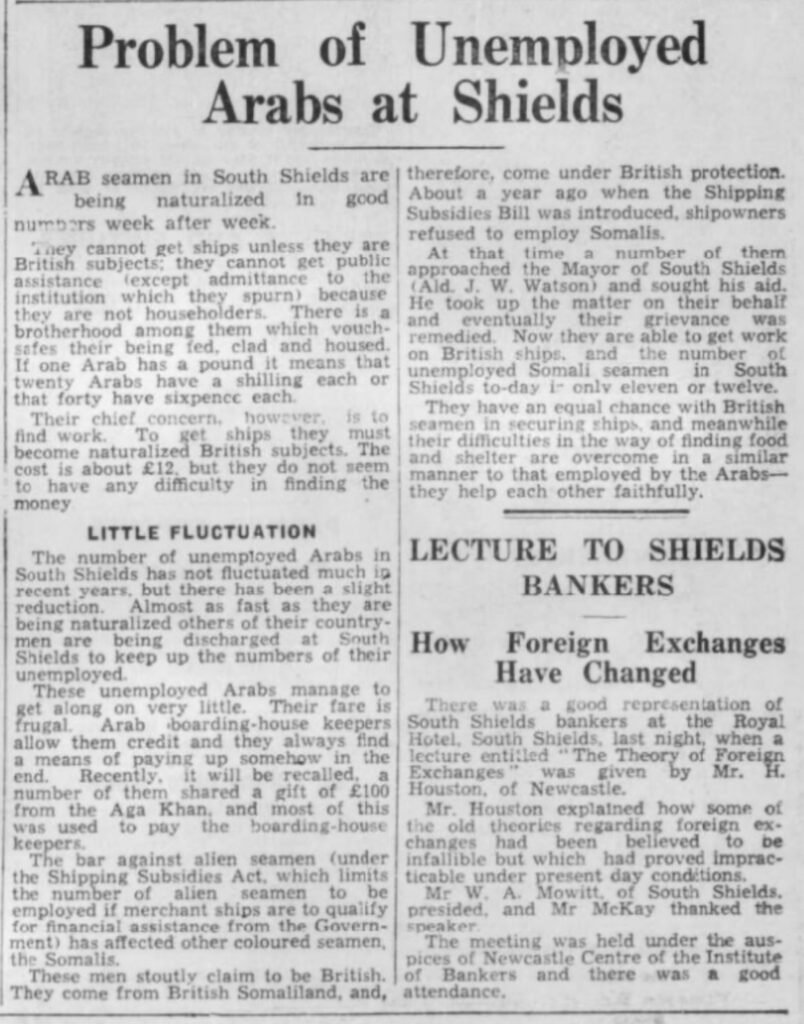

A result of the implementation of nationality based legislation was an increase in the number of applications for naturalisation from the Arab community.

Shields Gazette 29/08/1917

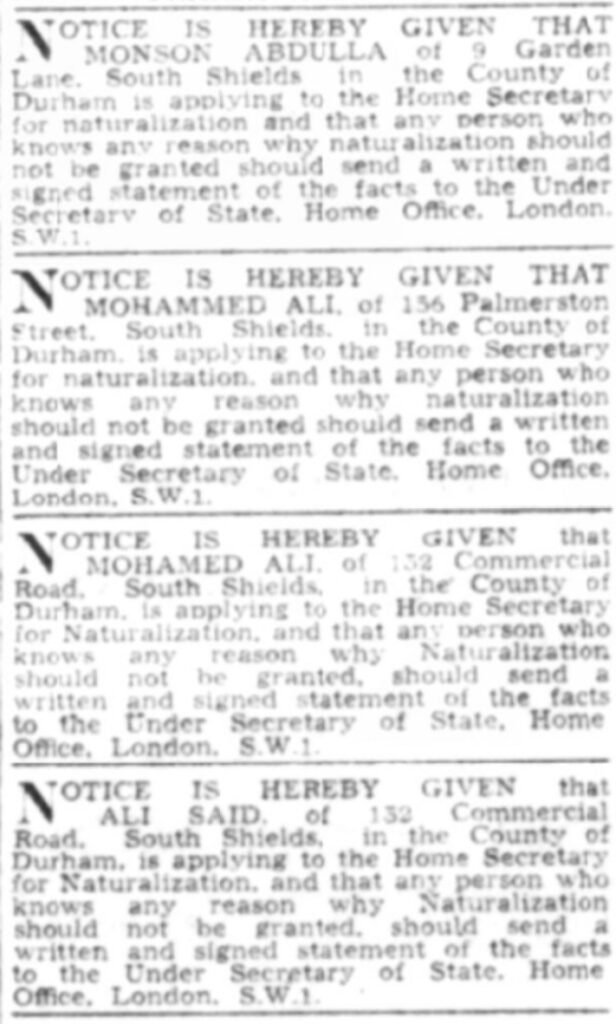

Hansard – Parliamentary debate – Wednesday 28 April 1926

Hansard – Parliamentary Record of Debate 14

the creation of a new problem

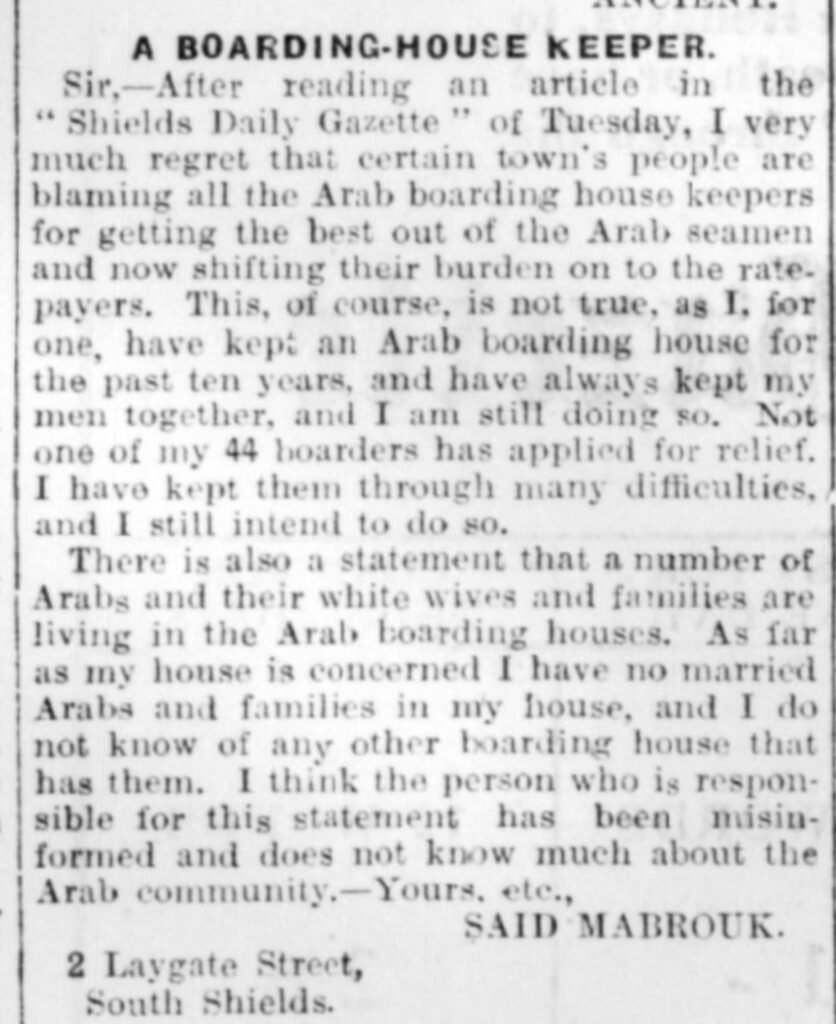

Attempting to monopolise the jobs market in favour of white men by scrutinising the legal status of every Arab ashore, succeeded in restricting them from work. They were then faced with the issue that the Arabs had no work which put them at risk of being a burden to the rate payer.

(c) The Shields Gazette 23/10/1936

Post war destitution – surplus to requirements

(c) The Shields Gazette 20/09/1930

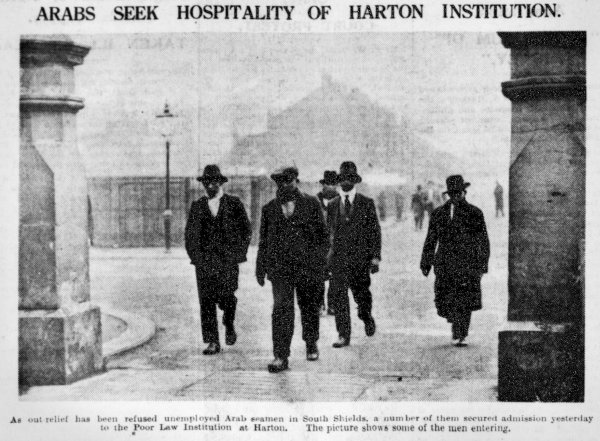

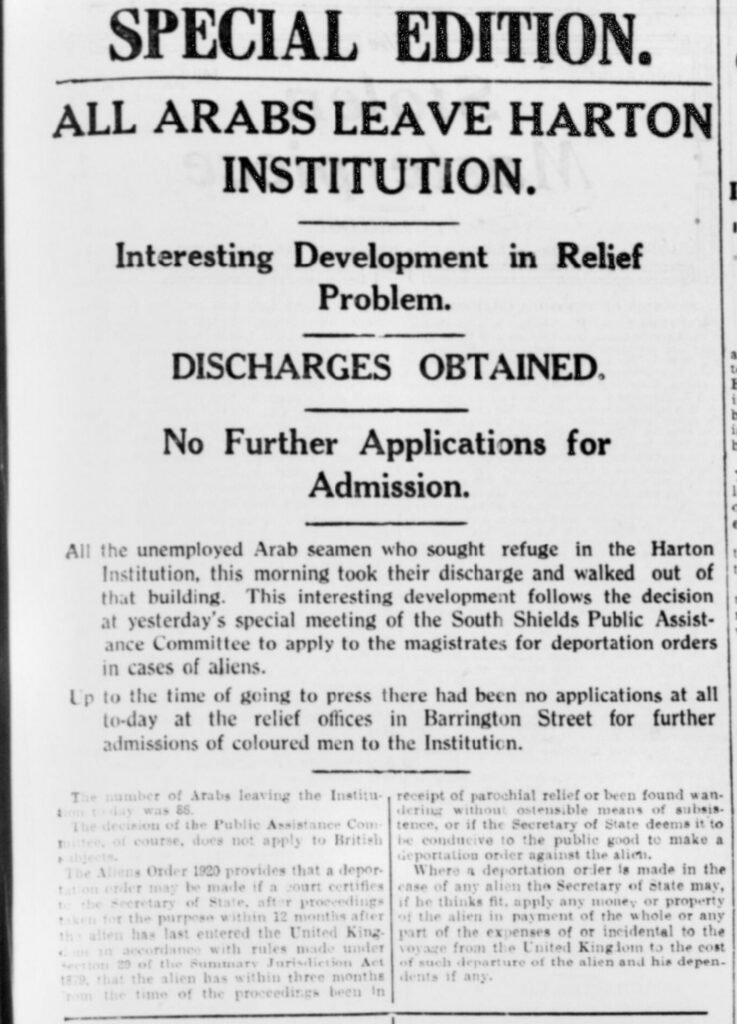

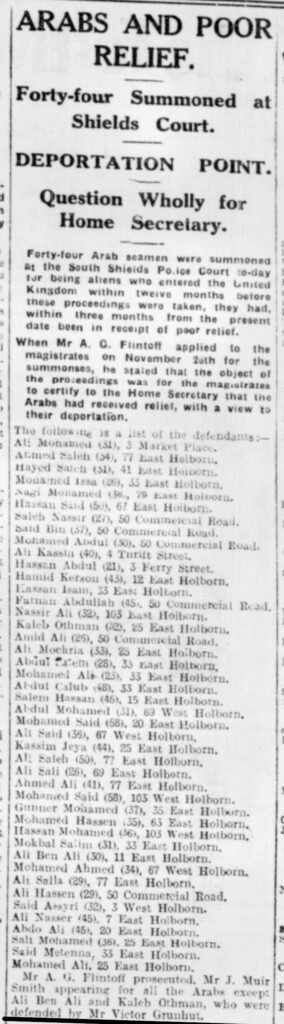

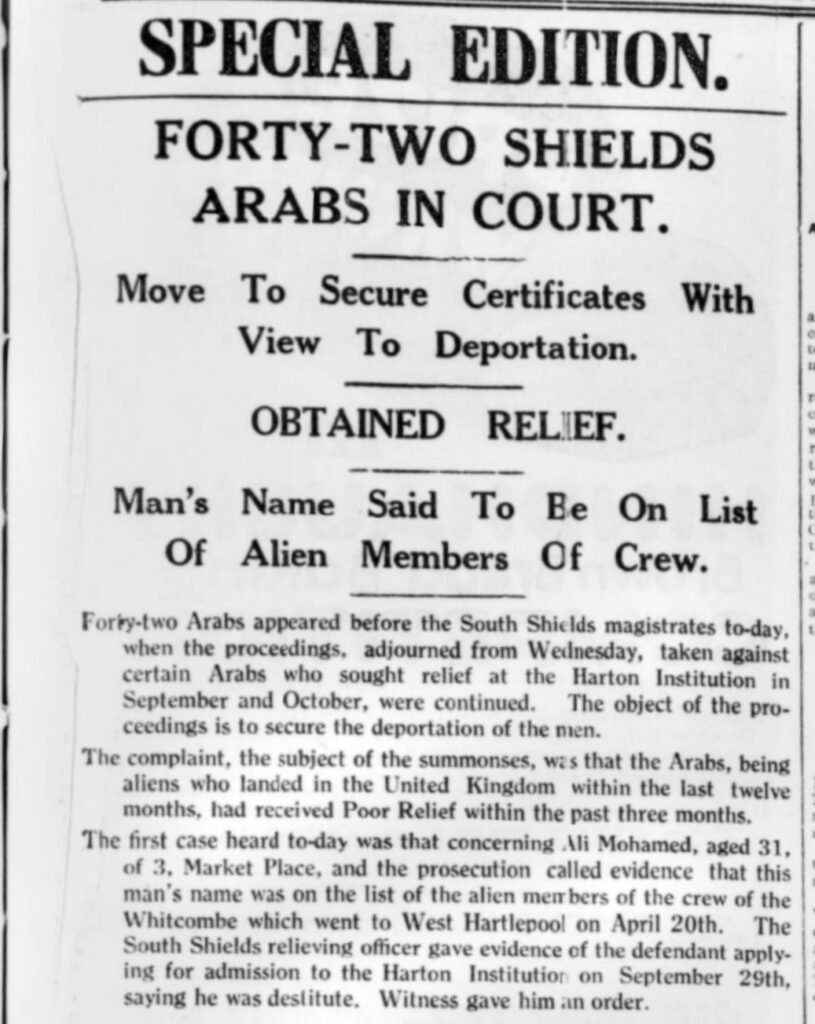

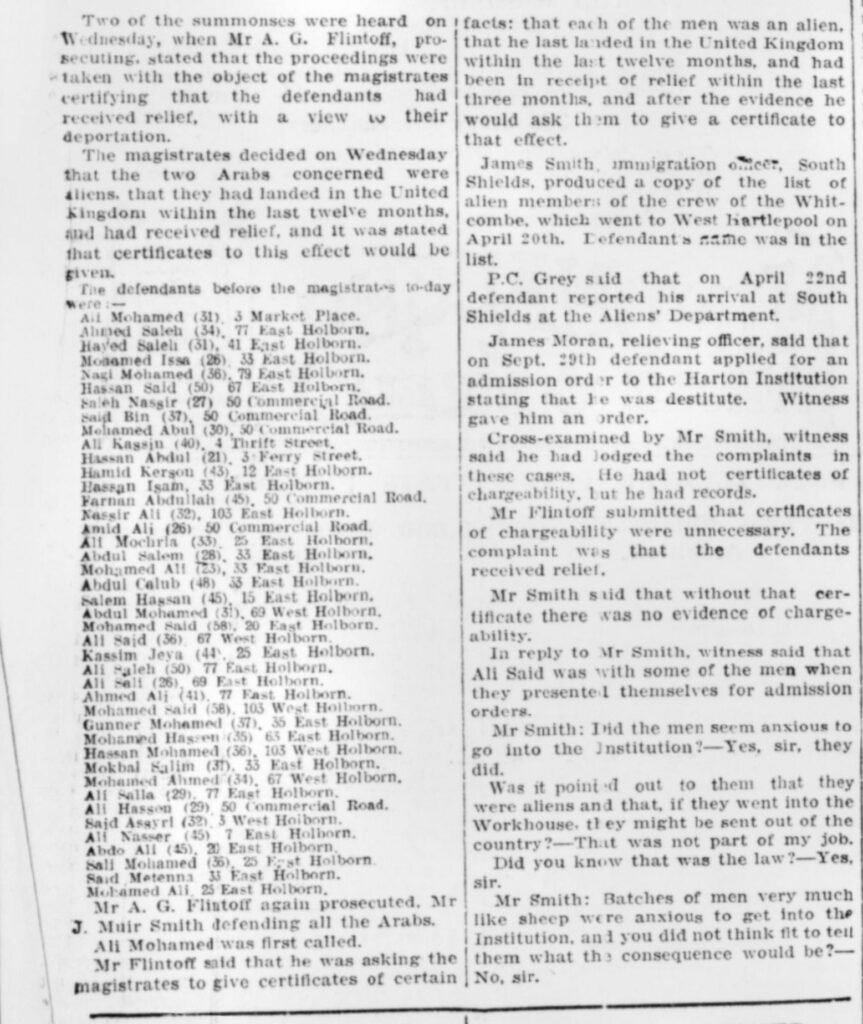

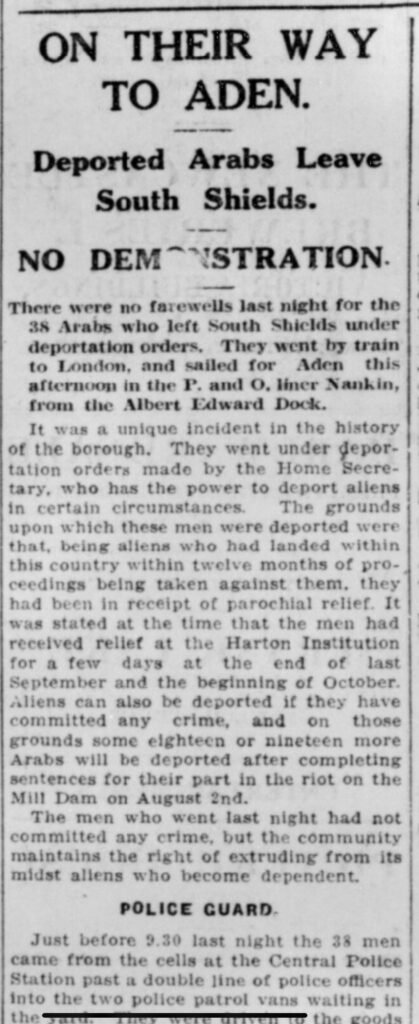

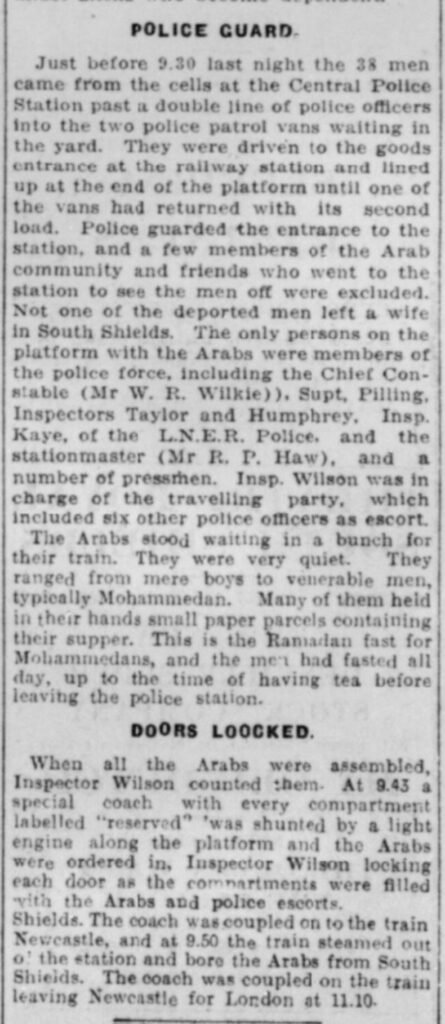

As the pressure continued, unable to obtain jobs, the Arab Seamen were unable to continue paying the boarding house keepers for their rent, food and basic needs. Many boarding house keepers bankrupted themselves trying to maintain their boarders, some of whom they had supported for over a year. Facing no other options, Arabs began to apply for indoor relief (and outdoor relief) at Harton Institution. This was the equivalent of state welfare. The result was uproar in the local community and a new vulnerability for Arabs some of whom learnt the hard way that new laws meant any new arrival to England could be deported for seeking relief if sought within 12 months of arrival.

(c) The Shields Gazette 03/10/1930

(c) The Shields Gazette 26/11/1930

(c) The Shields Gazette 10/12/1930

In the following news story, an official admits that he deliberately omitted to tell the Arabs that taking aid may lead to their deportation – which it then did.

(c) The Shields Gazette 12/12/1930

“Deport them”

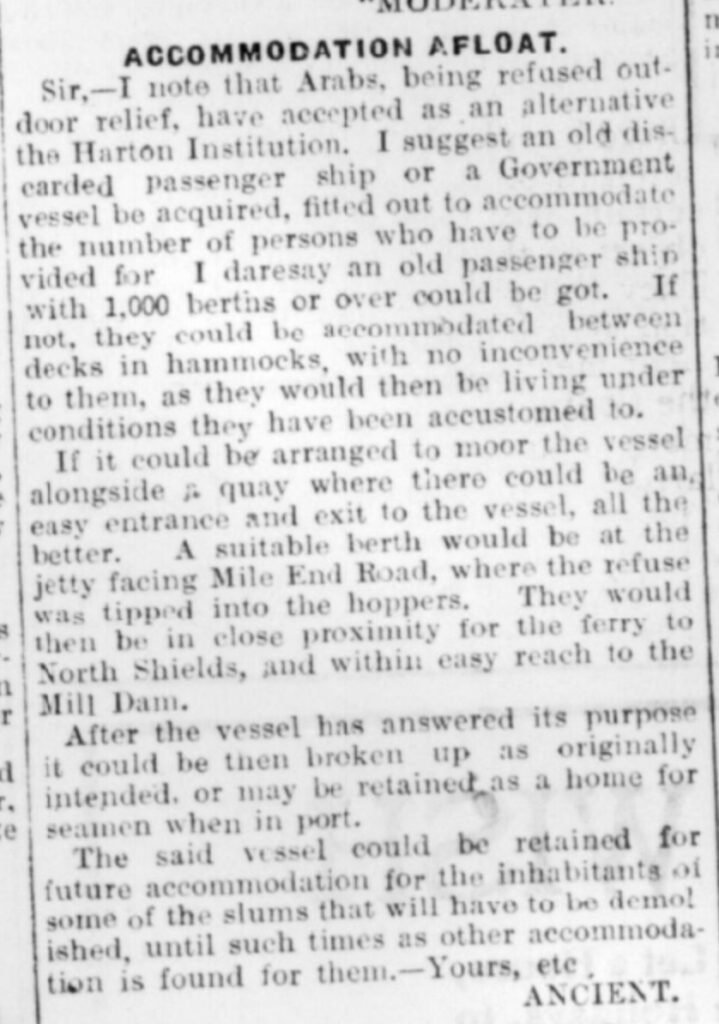

With their war service long forgotten or completely disregarded, letters in the Shields Gazette often stuck to the same theme of deporting destitute Arab seamen rather than allow them to seek help or financial support from the state. “One writer even suggested that the Arabs should be accommodated in a discarded passenger ship or government vessel that might also be used for other Arabs to allow slum clearance in Holborn.”

(c) Shields Gazette 02/10/1930 (below)

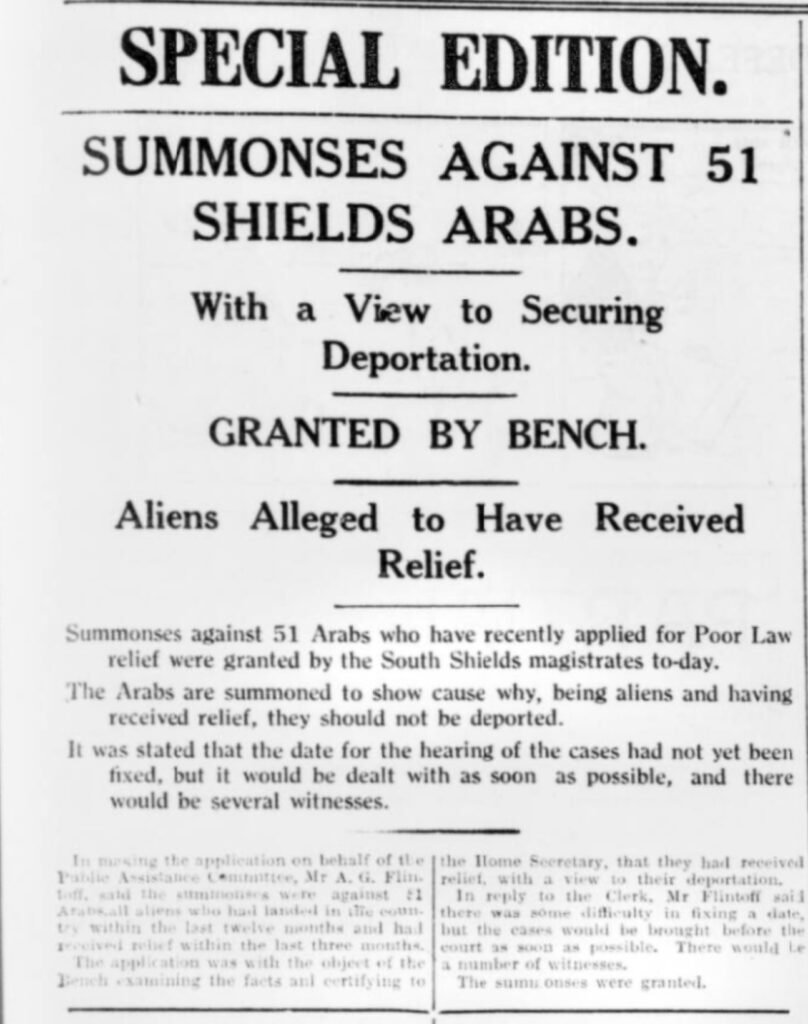

arabs deported

(c) The Shields Gazette 30/01/1931

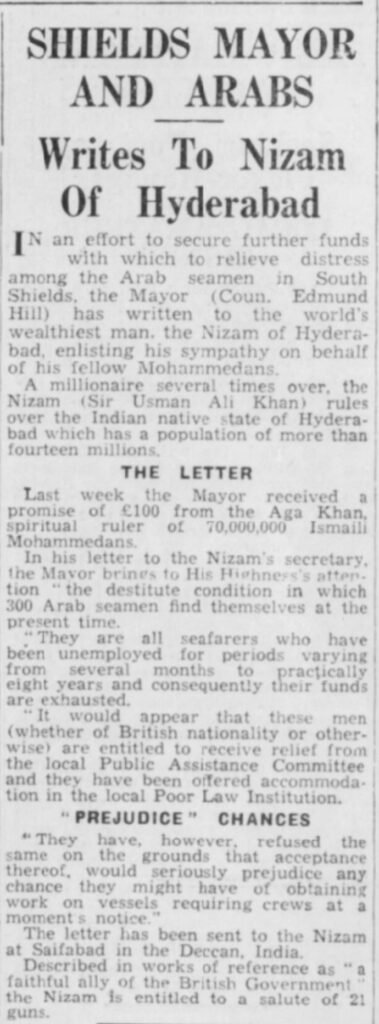

limited assistance

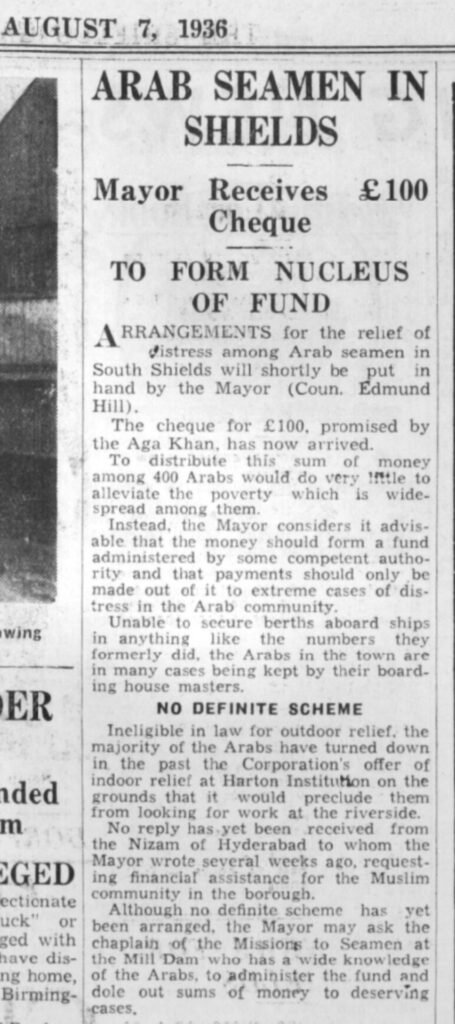

As events unfolded, the mayor, councillor Edmund Hill wrote to international islamic leaders seeking financial assistance for the destitute Arabs and received a donation from the Aga Khan which was used to form a relief fund.

(c) The Shields Gazette 06/06/1936 and 07/08/1936

- Lawless, R.I. (1995). From Taʻizz to Tyneside. p. 23 ↩︎

- Ibid., 26 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- ↩︎

- ↩︎

- Chandran, R. (2021). Once British Always British: stories of Indian and Yemeni sailors in Britain in the 1920s – Tamasha. [online] Tamasha. Available at: https://tamasha.org.uk/blog/tamasha-digital/once-british-always-british-stories-of-indian-and-yemeni-sailors-in-britain-in-the-1920s/. ↩︎

- (c) The Shields Gazette https://www.shieldsgazette.com 28/09/1927 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Chandran, R. (2021). Once British Always British: stories of Indian and Yemeni sailors in Britain in the 1920s – Tamasha. [online] Tamasha. Available at: https://tamasha.org.uk/blog/tamasha-digital/once-british-always-british-stories-of-indian-and-yemeni-sailors-in-britain-in-the-1920s/. ↩︎

- Parliament.uk. (2025). Steamship ‘Benecia’ (Arab Seamen) – Hansard – UK Parliament. [online] Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1926-04-28/debates/fbf5934e-158b-47c1-a2e5-65f7eb7ecf9c/SteamshipBenecia(ArabSeamen) [Accessed 28 Jul. 2025].

↩︎ - (c) The Shields Gazette https://www.shieldsgazette.com ↩︎