1930s Riots

2nd August 1930

On April 29th, 1930, thirteen Somali firemen were viciously beaten by white seamen when they attempted to sign onto a ship in North Shields, across the River Tyne. And on August 2nd, 1930, a white man signing onto a ship at Mill Dam hurled a racial slur at Yemeni protestors.1 On the 2nd of August 1930, economic problems amplified by stiff competition for jobs and fuelled by racism led to what is largely known as the ‘race riots’ of the 1930s.

The Build up – restrictive legislation and a hate campaign

1920 – The Aliens Order

“Any sailor or fireman seeking employment was required to obtain a card known as the PC5, from the Sailor’s and Firemen’s Union and get it stamped by the union and Shipping Federation. ” 2

1925 – Registration Order – Special Restrictions Order

The purpose was to classify non-white British colonial seafarers as “aliens” (foreigners), unless they could prove their British nationality—even if they were already British subjects.

1929 – NUS become more Aggressive towards arabs

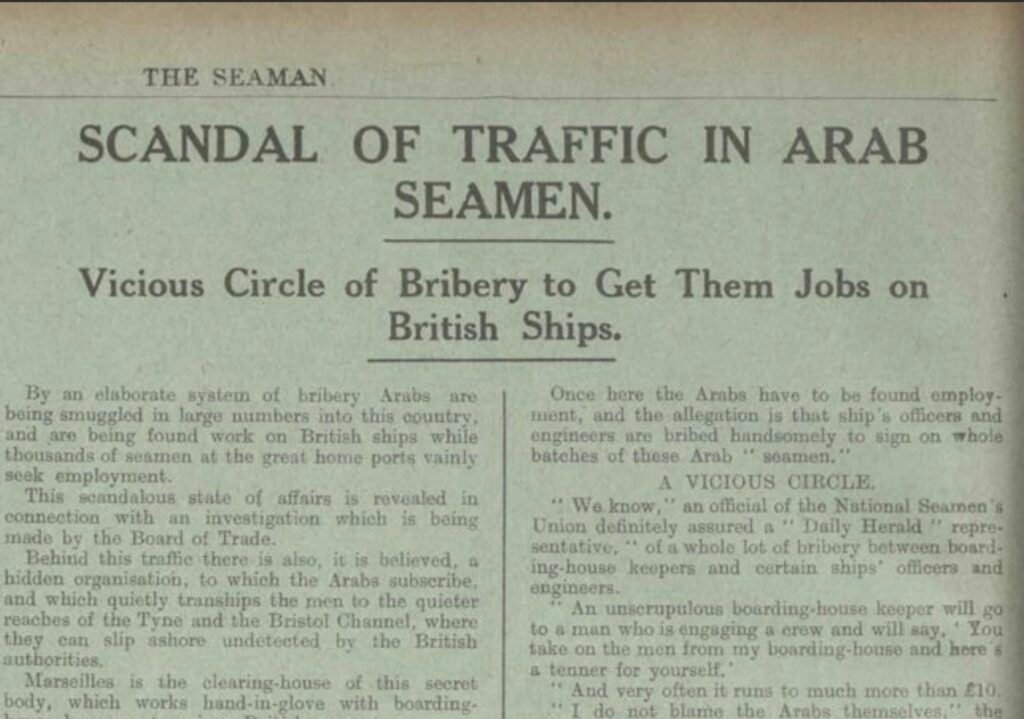

A deputation is sent to the Board of Trade on the subject of Arabs taking jobs on British ships. Arabs are consistently targeted in NUS publication ‘The Seaman’.

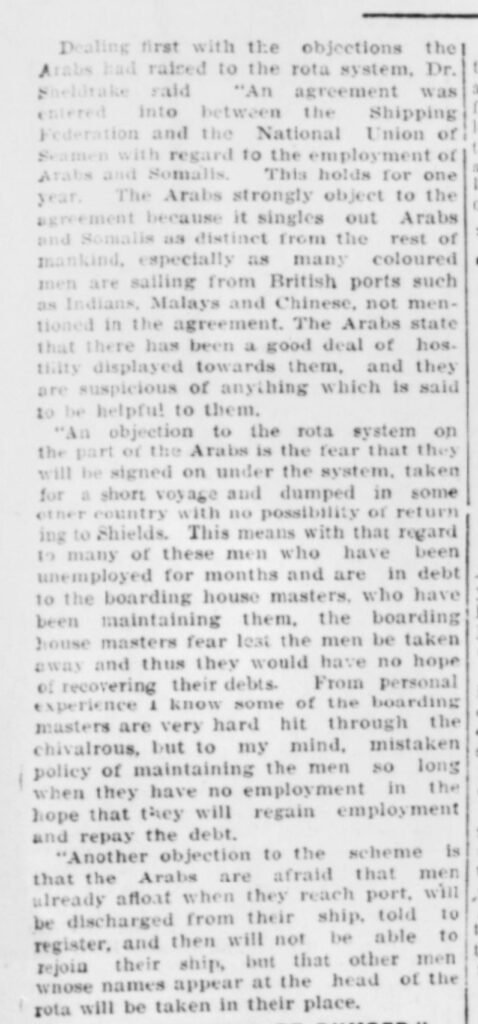

March 1930 – Khalid Sheldrake visits South Shields

Life President of the Western Islamic Association visits to express his support for the Arabs,

April 1930 – NUS send another deputation to the board of trade

This time they include representatives from the north-east-coast, the Humber, Bristol Channel and Antwerp.

May 1930 – the Seaman’s Minority Movement take up the arab cause

The movement called for better wages and working hours. Opposed the NUS and had leading ties to communism. They began holding meetings at the Mill Dam.

July 1930 – The rota system is born

“a rota system of registration for Arab (and Somali) seamen at Cardiff, South Shields and Hull.”

August 1930 – Violence Breaks Out

Pressure from the NUS against pushback from the Seamens Minority Mission, racial prejudice, economic depression, restrictive and controlling racialised legislation and antagnomism reach a head resulting in the riots of 1930.

1935 – The British Shipping Act

Pressure from the NUS and the Transport and Workers Union had ensured that in order to enjoy the government subsidy on merchant shipping, shipowners had to agree to employ only British crews.3.

Board of Trade Offices – Mill Dam, South Shields (c) South Tyneside Libraries

As with the 1919 riots, in 1930 Britain was still depleted of its resources after the war and at a time without welfare, people needed money to survive. British ship-owners would still undercut English sailors by employing Yemeni men who would do the most difficult jobs for less pay. Consequently, animosity brewed as work became harder to obtain and many English seamen, grew angry at the harsh conditions and misdirected their anger. Instead of blaming the shipowners, the Yemeni seamen were scapegoated.

The National Union of Seamen was complicit as it took issue with the employment of Yemenis making it difficult for Englishmen to find work. “‘The Seaman’ (the NUS newspaper) published a number of articles (…) in an attempt to discredit Arabs and praise the superiority of white crews.” (1)

In response to these articles, “Ali Said, one of the leading Arab boarding-house masters in South Shields, appealed to the Secretary of State for India against the attitude taken by the National Union of Seamen towards Arab and coloured seamen”(2).

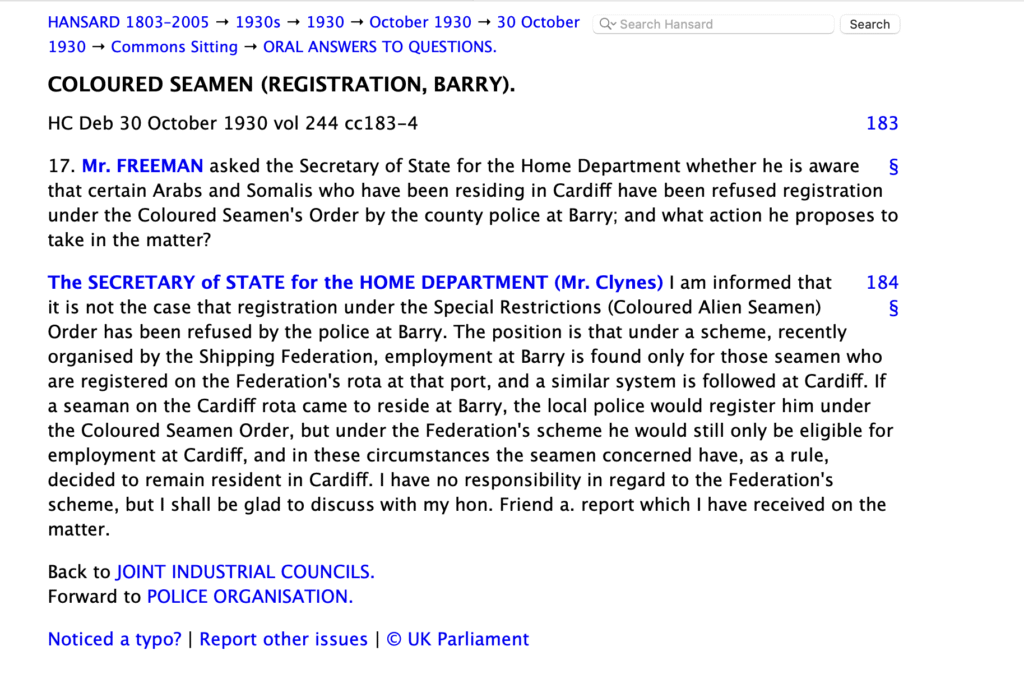

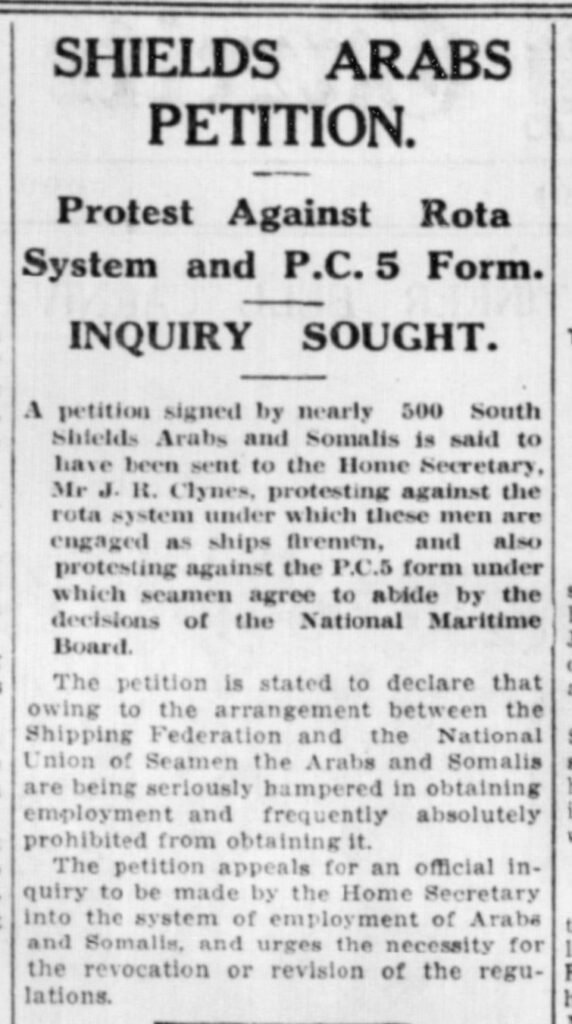

The introduction of a rota system in 1930 only for Yemenis and Somalis to register and report for work on the ships further sought to intensify relations and the situation. The Yemeni men, many of whom were British citizens were unwilling to subscribe to a prejudicial system aimed only at singling them out and making employment more difficult. Those who were unable to register under the Special Restrictions Order in 1925 were therefore denied employment and were lost inside the system. Below is an excerpt from a parliamentary debate addressing the same situation with the Arab community in Cardiff, 1930.

Records of conversation in Parliament about the destitution of those unregistered and unable to register or gain employment. 5

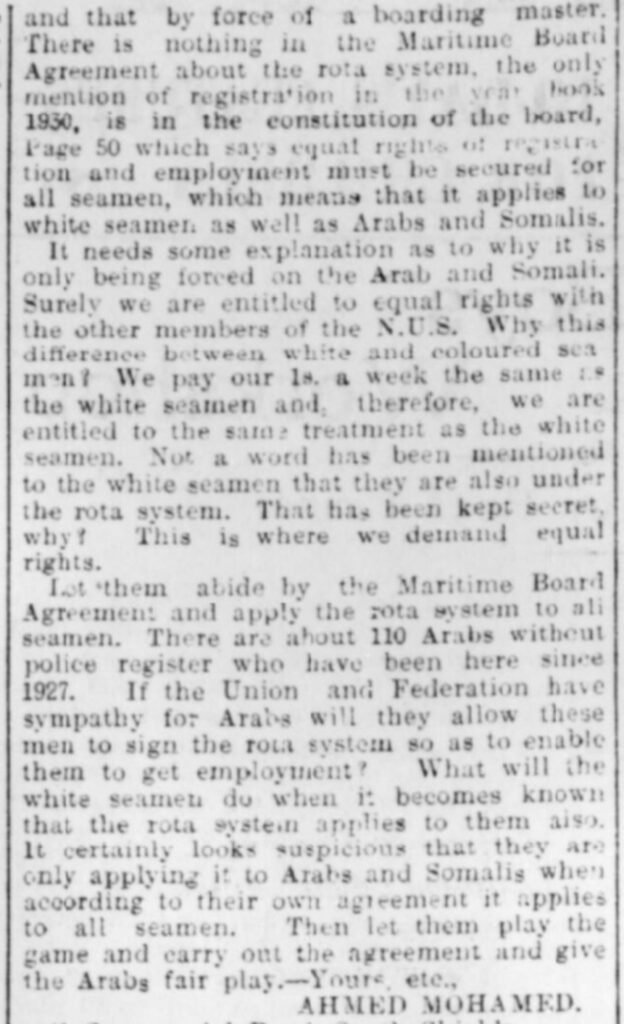

Many affected seamen mentioned in letters to the Shields Gazette that they did not seek preferential treatment to white seamen and had this system been for all seamen they would have complied. It was clear that this was one of the first racialised immigration policies to be implemented in 20th century Britain.

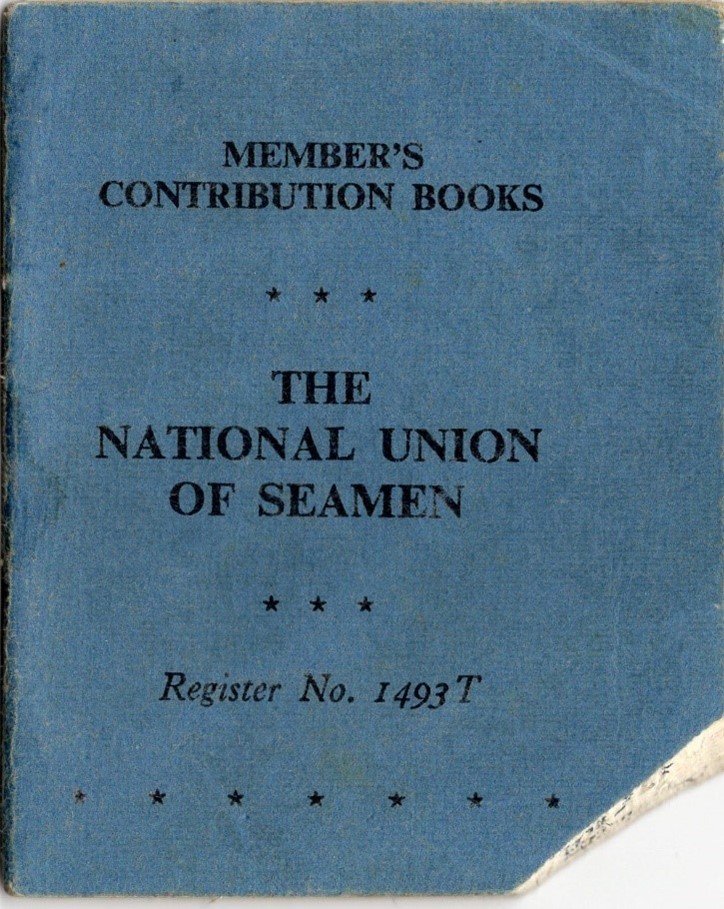

The PC5 system- labour control

The PC5 or ‘Particular Contract 5’ was designed to regulate working and pay terms and conditions for seamen. It also regulated how seamen were hired.

Lawless states: “The machinery used to tighten control over the labour supply was the ‘PC5′ system. (…) Under this system any sailor or fireman seeking employment was required to obtain a card, known as a PC5, from the Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union and get it stamped by both the union and the Shipping Federation.”

“The Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union of course only accepeted its own members and insisted on them being fully paid up. This meant real hardship for many seamen who during a period of high unemployment, had been out of work for long periods. In practice the PC5 system meant that the owners agreed to employ only members of the Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union and in return the union agreed to keep the men in order. Not surprisingly, there were many protests.” 6

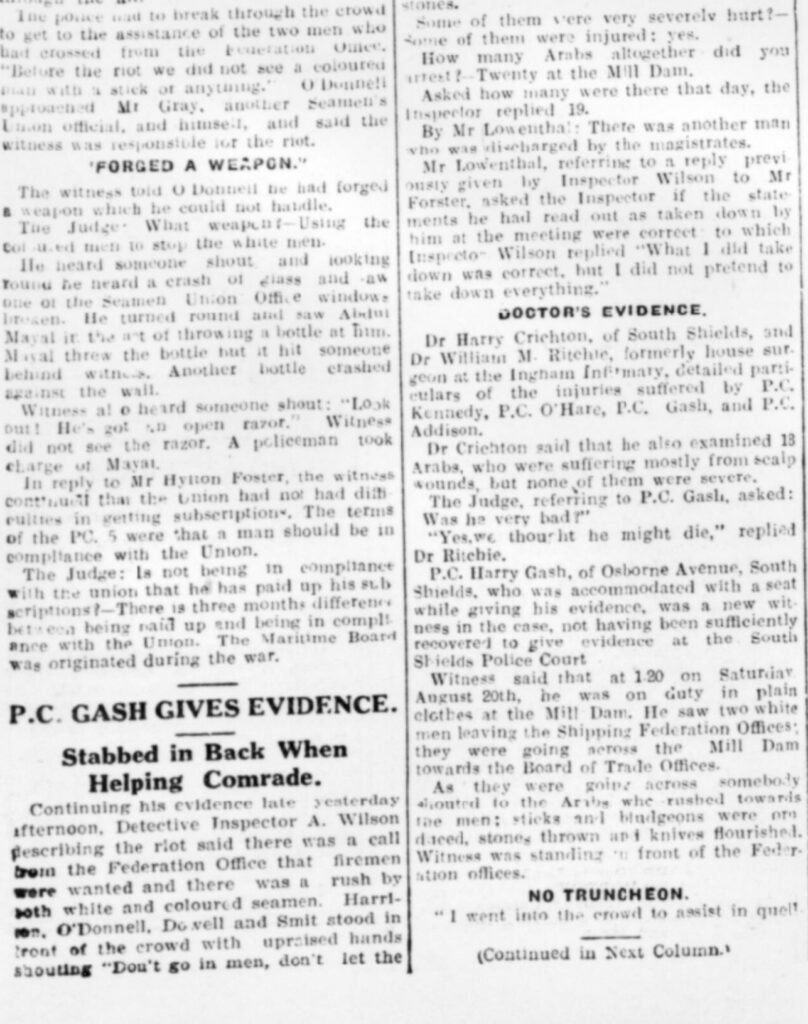

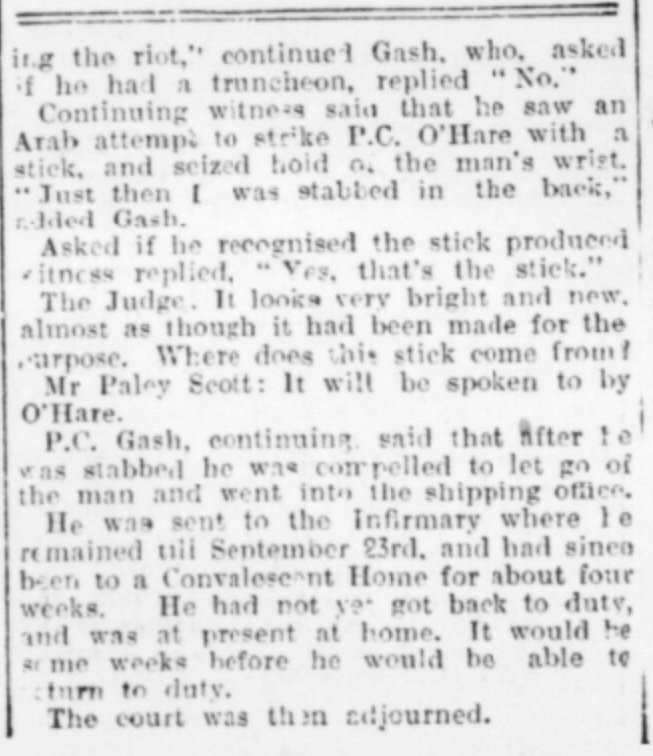

(c) The Shields Gazette 05/09/1930

The Rota System

“In 1930, the National Union of Seamen introduced a rota system that targeted only people of color, primarily Yemeni and Somali seamen. They were required to re-register with the union each time they finished work on a ship, before they were able to work on another. The rota was criticized as racially discriminatory by Yemenis, Somalis, and by the Minority Movement, a multiracial Communist organization. In protest, scores of Yemeni and Somali seamen, as well as some white allies, refused to sign on. “7

“The Joint Supply Office (…) was to keep a register in two parts, one for Arabs and the other for Somalis. Officers were to have complete liberty to determine the nationality of the crew.”

“He (the seaman) was required to produce either a police registration certificate or a British passport together with discharge from one more more British vessels. (…) he was then issued with a pink numbered registration card to which his photograph was attached and was instructed to report at the office every fourteen days. The date would be entered in the register and marked on the back of his registration card. When an Arab or Somali crew was required the relevant number would be called up for selection giving priority to seamen with the lowest number on the register who were recorded as unemployed.” 8127

uncertainty

Due to the ongoing campaign waged by the NUS against the Arabs, many were sceptical of any scheme involving them that the union proposed. Rumours circulated around that the scheme was a secret plan to take Arabs and abandon them in far off ports, not allowing them to return home. This paranoia grew and many refused to sign up to the rota system because of it. Ali Said, prominent boarding house master was thought by authorities to be responsible for the circulation of these rumours which to many felt like real threats. The Gazette letters of this era were full of calls for the Yemenis deportation and it is understandable that there would have been genuine fear and apprehension regarding such a scheme. There is no hard evidence supporting these allegations against Ali Said.

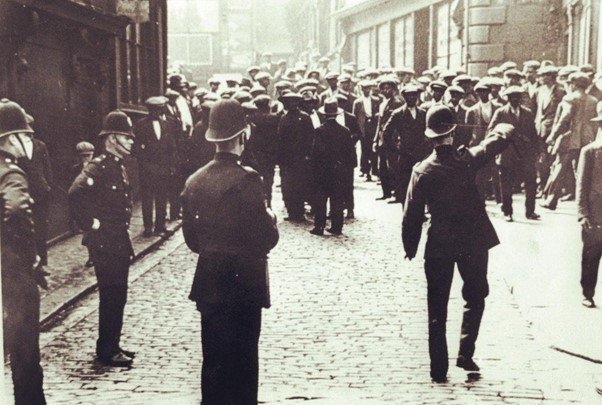

‘The Riot’ – August 4th 1930

11am – Minority Movement meeting 9

“About 150 Arabs and 100 white men were present and 15 policemen were on duty stationed in small groups on and round the Mill Dam”.

12:32pm – Superintendent Pilling telephoned for 6 more policemen

The mood was at fever pitch and the police could see trouble coming.

Before 1pm – Officials of NUS and Shipping Federation shout for firement

“A number of white men (….) and a rush of Arabs into the office” Members of the Seamen’s Minority Movement stood in front of the crowd. “White men were selected for the firemen’e firemens posts (…) Arabs had to eject”ted from the Shipping office”10

1pm – Hamilton and Bradford leave Shipping Federation Office with weapons.

“Hamilton and Bradford, left the Federation Office and Harrison told IInspector Wilson that one of them had something up his sleeve and that the other had a razor.” O’Donnell of the Seamen’s Minority Movement warned the police that there would be trouble if the white crew were selected for the Arabs jobs ‘and he wouldn’t be resposnible for it’11

1:20pm – The Shipping Federation call for firemen again.

There were calls from the Seaman Minority Movement and Ali Said, to obstruct and stop people from signing on. “Harrison, O’Donnell, Dowell and Smit stood in front of the crowd shouting, ‘Don’t go in men, don’t let the scabs sign on” 12Violence breaks out.

Factors which contributed to the riot

1. The national union of seamen

Despite the fact that the National Union of Seamen (NUS) accepted Arabs as members and took their money for membership, the NUS played an active role in trying to restrict their ability to ship out. Membership to the NUS was vital for any seaman to be able to work on a ship, so to actively campaign against a section of its own membership whilst still accepting that membership is a double standard that many white seamen themselves took issue with.

It relentlessly publishes articles in ‘The Seaman’ scapegoating and blaming the Arab seaman for the unemployment of the white seaman.

“Le Touzel (manager of ‘The Seaman’) denounced the Arab boarding-house keepers as parasites and declared that the NUS intended to eliminate them as they were nothing less than crimps.”13

Neglecting to focus on the overall, global decline of shipping after the First World War which affected all seamen regardless of their colour. It sent frequent deputations to the Board of Trade seeking to restrict the ability of Arab seamen to take up work, preferring to take up white men of different professions than to take experienced Arab firemen.

In April 1930 the National Union of Seamen sent another deputation to the Board of Trade (…) Allegations of bribery and corruption to secure employment and of social abuses due to the alliances of Arab with white women were repeated.”14

“He (Khalid Sheldrake) pointed out that the British Empire was the largest Islamic power in the world and that King George V had more Muslim subjects than Christian.”15

2. The Seamen’s Minority Movement

The Seamen’s Minority Mission took up the cause of the Arab seaman and campaigned for equal treatment on their behalf. Initially, their tactics and picketing were peaceful but as time progressed they became more aggressive with their attitude and their rhetoric. They actively urged seanmeb not to sign up for the PC5. They used inflammatory language to describe people who signed on to the PC5 scheme and acquired work.

“The seamen are fighting this triple alliance of shipowners, Labour Government and the Fascist Union of Seamen, the NUS. To smash this alliance and win through to victory (…) effective action must be taken to prevent scabs signing on.”16

They appeared to have recruited around 300 17members in South Shields. Lawless states “at the end of July O’Donnell proposed that pasive picketing should be replaced by forcible efforts to prevent scabs shipping out.” (135). This increase in temperature was an evident factor in what caused violence to later erupt on 04/08/1930. They incited the Arabs and were themselves ‘militant’ and if you add into this cocktail of tension racism – the results are not a surprise to anyone.

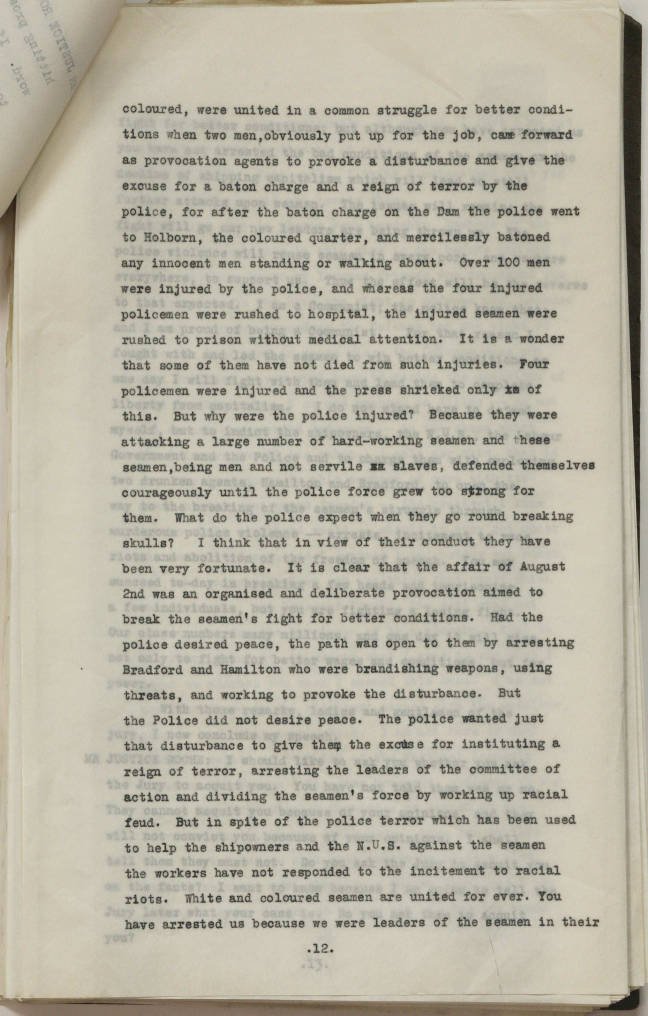

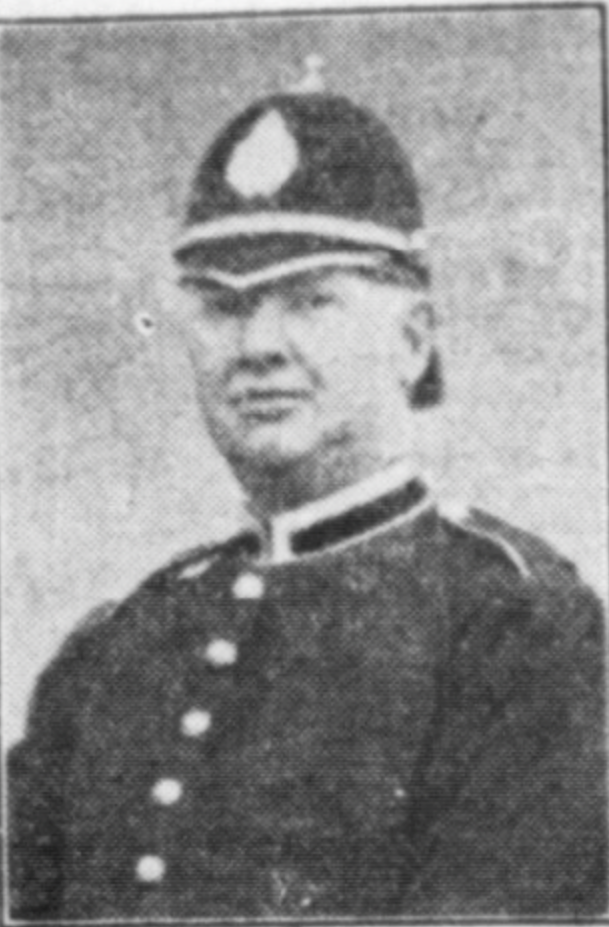

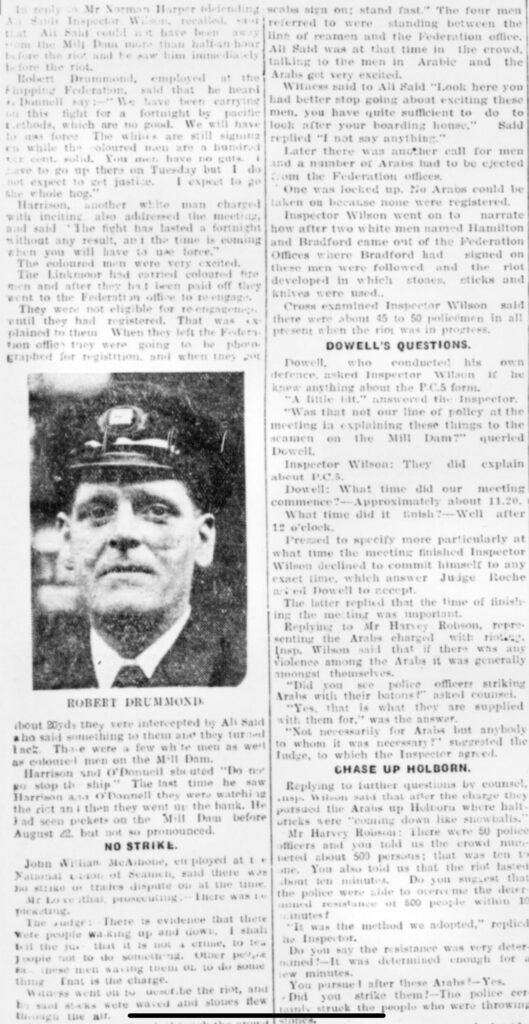

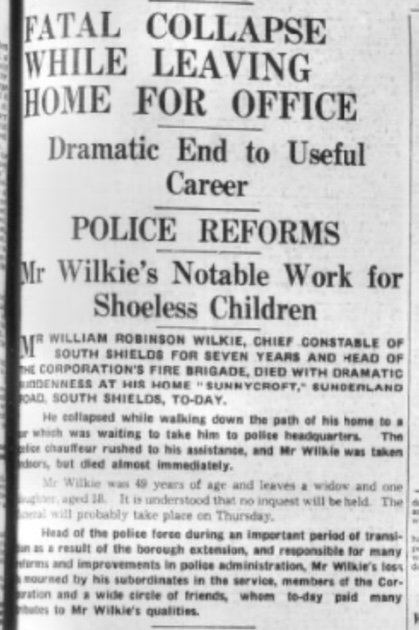

3. The police

The police had allowed the picketing activities of The Seamans Minority Movement to go ahead despite knowing the lines upon which they were campaigning.

(c) The Shields Gazette – Chief Constable W R Wilkie

““Detective constable Atkinson admitted under cross-examination that no attempt was made to search the Arabs for weapons when they tried to occupy the Federation Offices before the fighting broke out.”18

It is arguable that the police allowed the events of the 2nd of August to play out in order to regain control over the situation regarding the Seamen’s Minority Movement and as an opportunity to reign in the influence of Ali Said over the Arab community.

4. Ali Said

Ali Said was a prominent boarding-house keeper and very influential amongst the Arabs in South Shields. One of the first to arrive and establish himself in the town, he was deeply opposed to the PC5 and rota system and allied himself with the Seamens Minority Movement in opposing it. The police were weary of the extent of the influence he had over the Arabs in general and specifically in their opposition to the system. We know that he actively persuaded Arab seamen looking to re-engage on their ship SS Linkmoor not to sign the rota. “The Linkmoor which normally carried an Arab stokehold crew, sailed with white firemen.”19

This would obviously inflame the tension amongst seamen, sone of whom hadn’t had a ship for 18 months. Lawless says in his book, from Taiz to Tyneside: “The police accused him (Said) of moving among the Arabs at the Minority Movement’s meeting and inciting them.”

He goes on

“Although the evidence against Ali Said was not particularly strong, he received the harshest sentence of any of the men arrested; sixteen months’ imprisonment and deportation.”

It seems that an example was made out of Ali Said as a warning against resistance to the Arabs and other boarding house keepers. Ali Said left behind a wife and child upon deportation to Yemen, his daughter never got to see her father.

Today, an exhibition exists in Newcastles Discovery Museum with an actor playing the role of Ali Said, an example of how much of an impact he had to be singled out and displayed in an exhibition 90+ years after he was forced to leave the country.

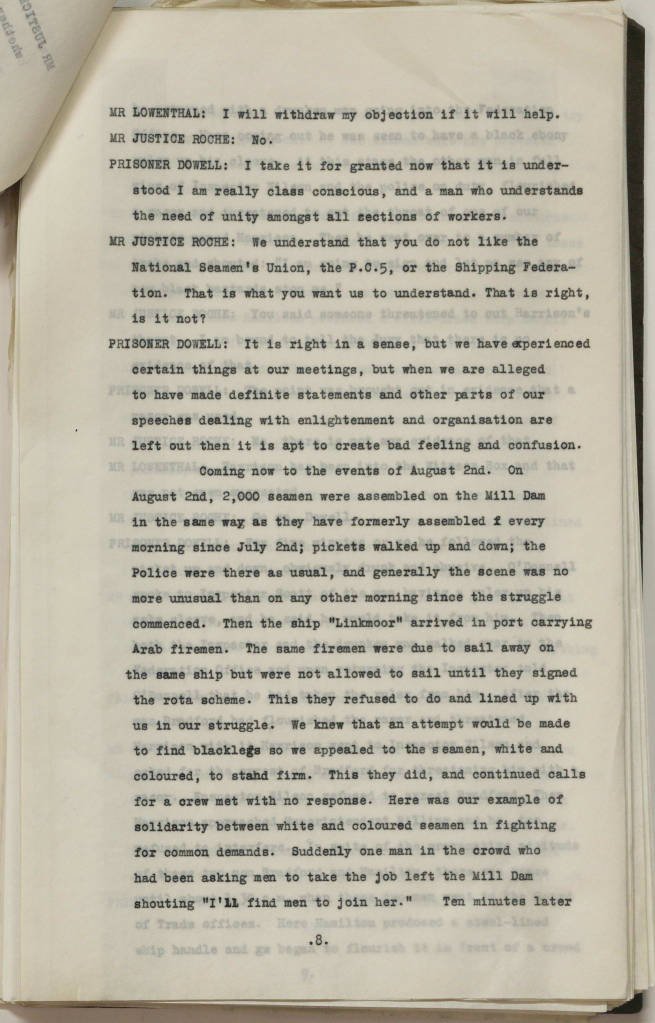

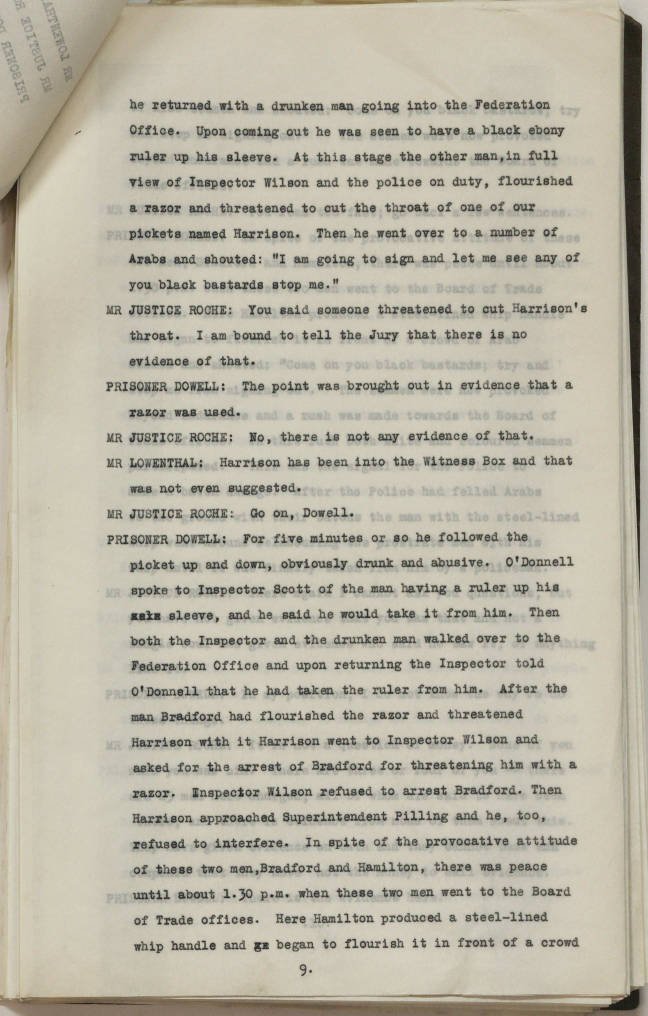

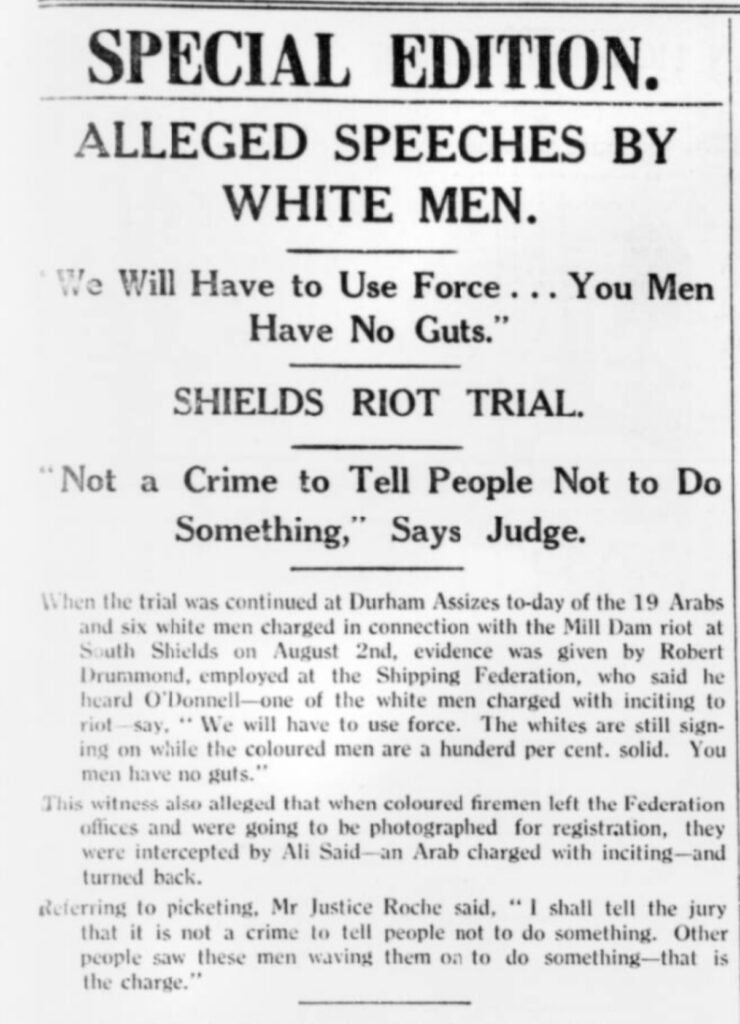

5. Bradford and Hamilton

The testimony which exists surrounding the role of Bradford and Hamilton Is contradictory and neither man was called to stand witness at the trial of those accused of rioting. This seems unusual, as they were accused of inciting the riots and provoking the Arabs causing the violence which followed. For certain there was some interaction between them and those at the picket. Dubious is whether they had weapons and if they had them the evidence does not point to them using them. Words were exchanged but the level of those words and the impact of those words remains contested.

Accusations:

“ Dowell, (…) stated that Harrison had complained to Inspector Wilson and Superintendent Pilling that the man Bradford had threatened him with a razor but that both officers refused to intervene.”20

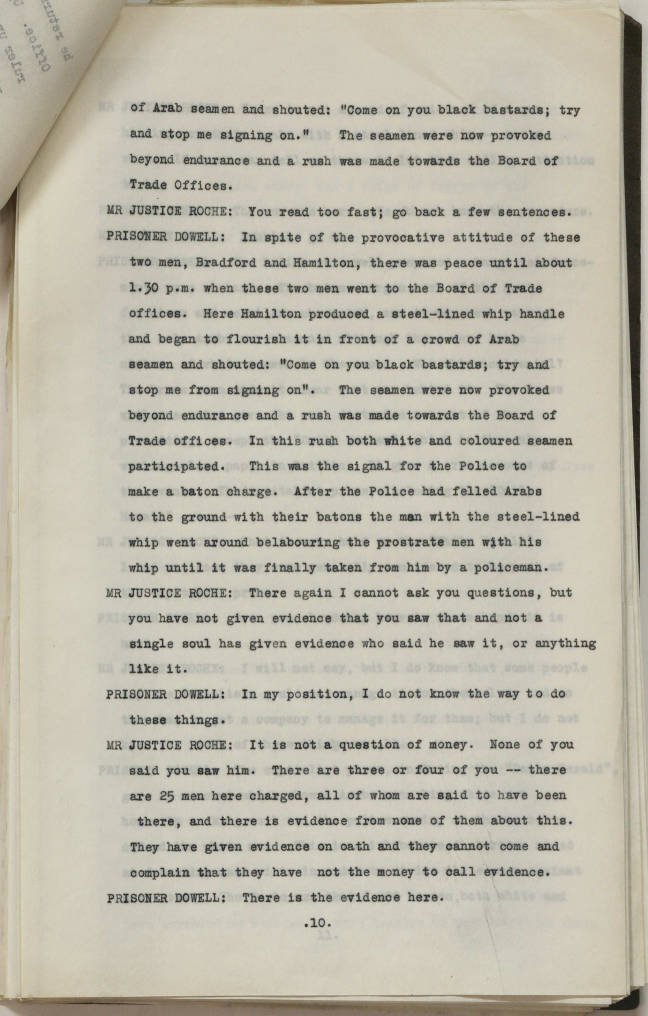

“Hamilton produced a steel-lined whip and flourished it before the crowd shouting ‘Come on you black ____; try and stop me signing on.’ Provoked beyond endurance, white and coloured men made a rush towards the Board of Trade Offices.”21

Defence:

“The police witnesses maintained that Bradford and Hamilton were unarmed and did not incite the Arabs but merely shouted to the pickets ‘I don’t care about you, I want my bread and butter’.

“None of the civilian witnesses stated that they saw either Bradford or Hamilton carrying any weapons.”

“The police witnesses maintained that Bradford and Hamilton were unarmed and did not incite the Arabs but merely shouted to the pickets ‘I don’t care about you, I want my bread and butter’.”

View of The Seaman’s Minority Movement:

“The Seaman’s Minority Mission claimed that Bradford and Hamilton, acting as agents of the NUS, deliberately provoked the pickets by threatening them with weapons in order to provide the police with the opportunity to intervene and smash the movement in South Shields.”

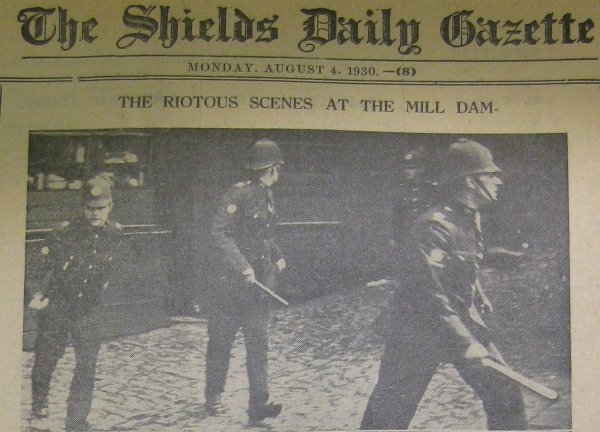

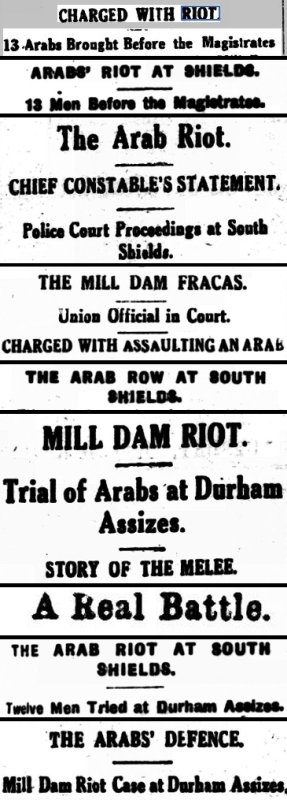

Prejudiced framing in newspapers

The Shields Gazette front cover – August 4th 1930 (c) The Shields Gazette

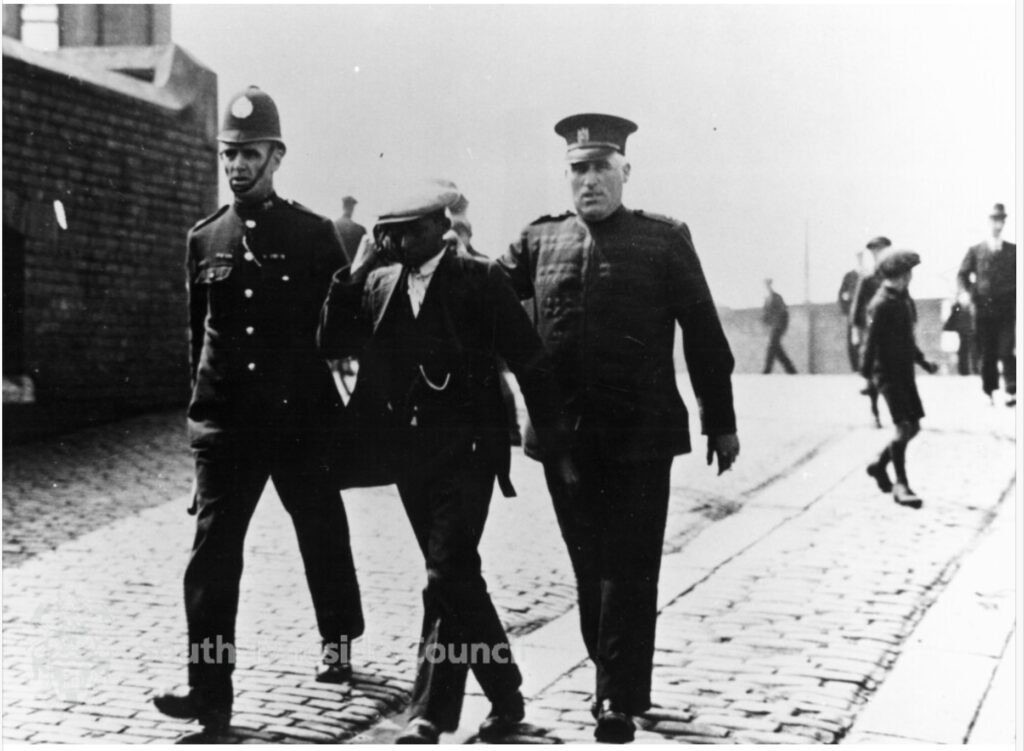

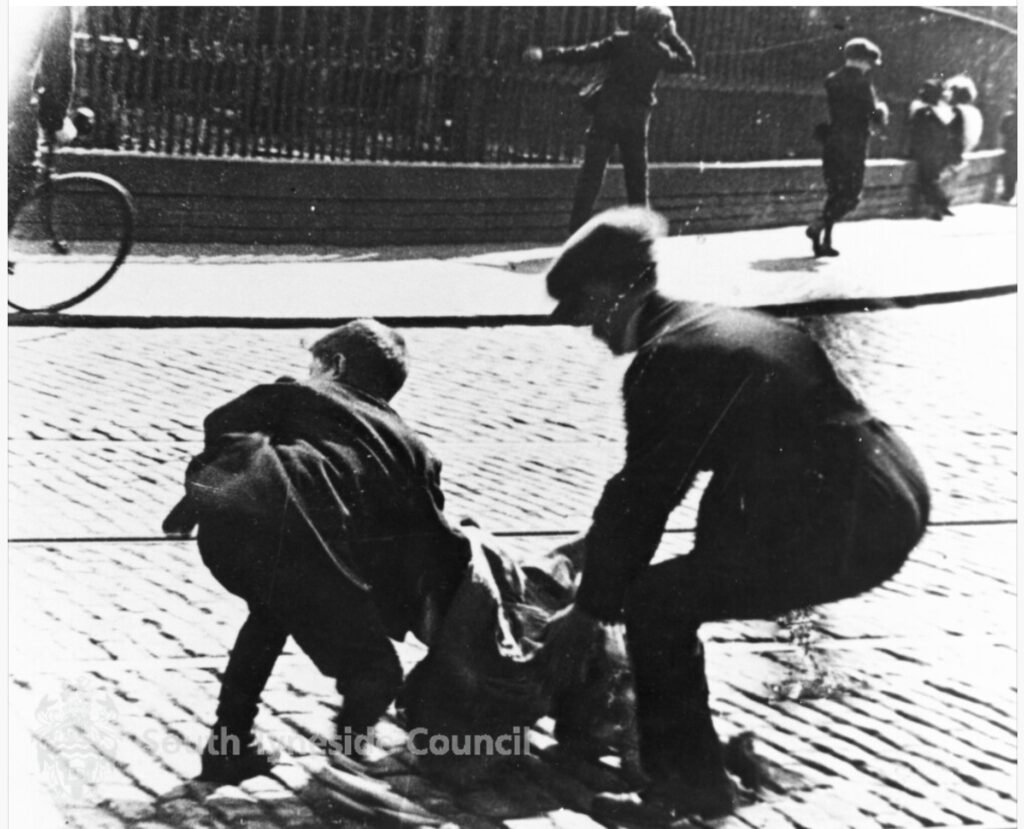

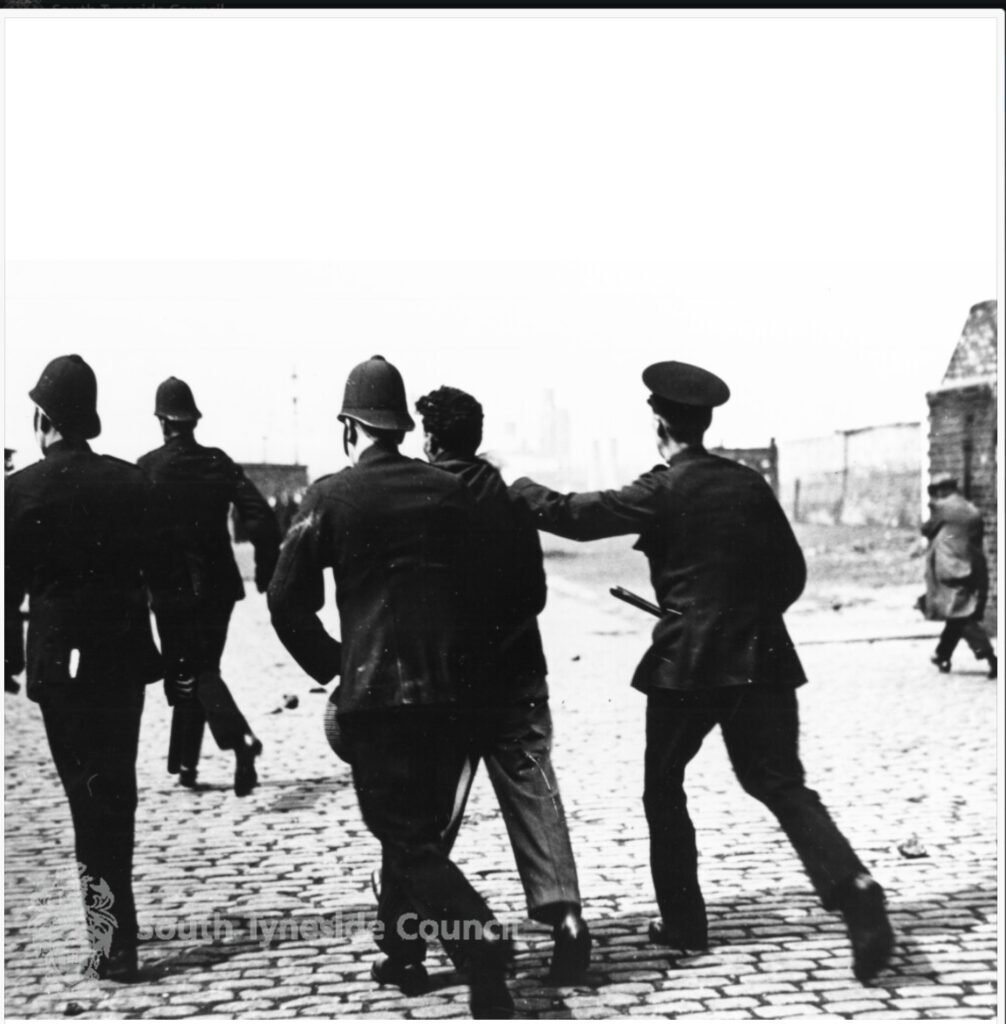

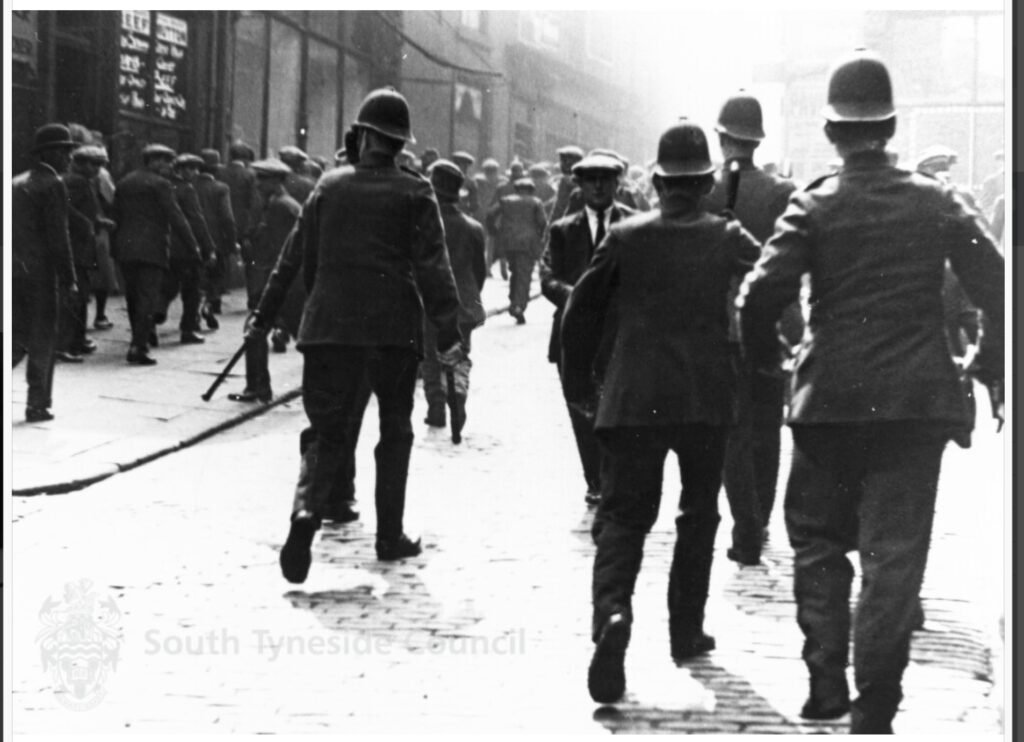

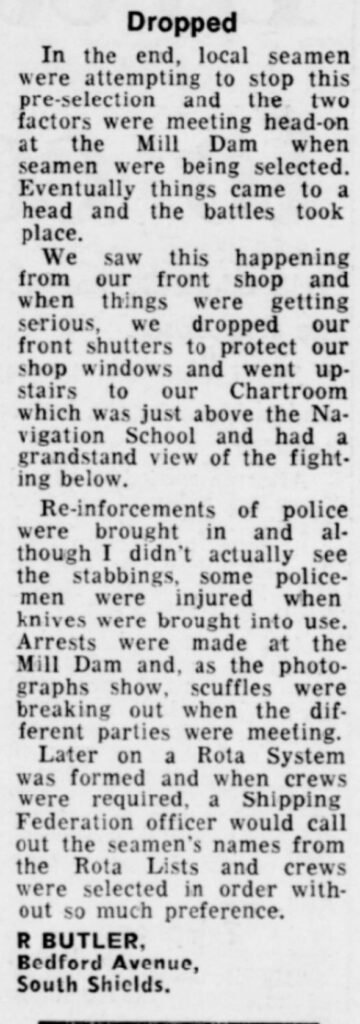

Photos from the riots

However, a common theme in the quotes taken from Yemeni men in the police report of the 1930’s riot is that of not having wanted trouble.

There were also Yemenis who helped the police during the riots including Mohamed Muckble who acted as a translator.

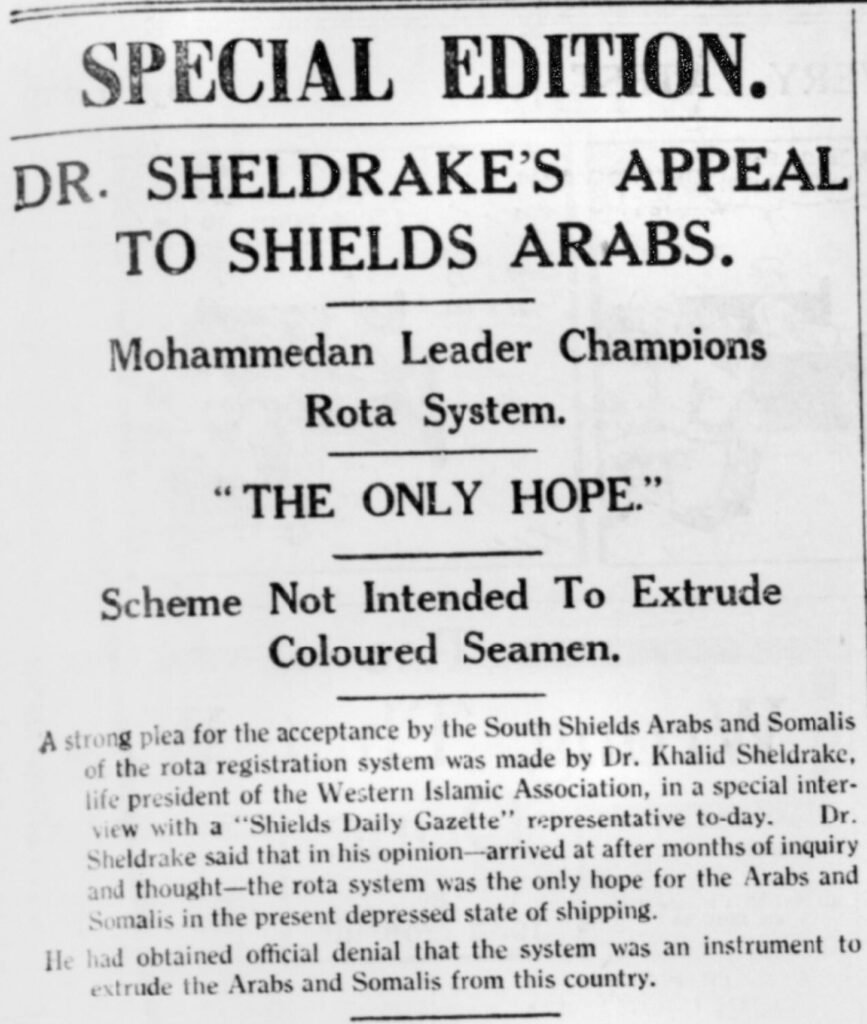

Aftermath

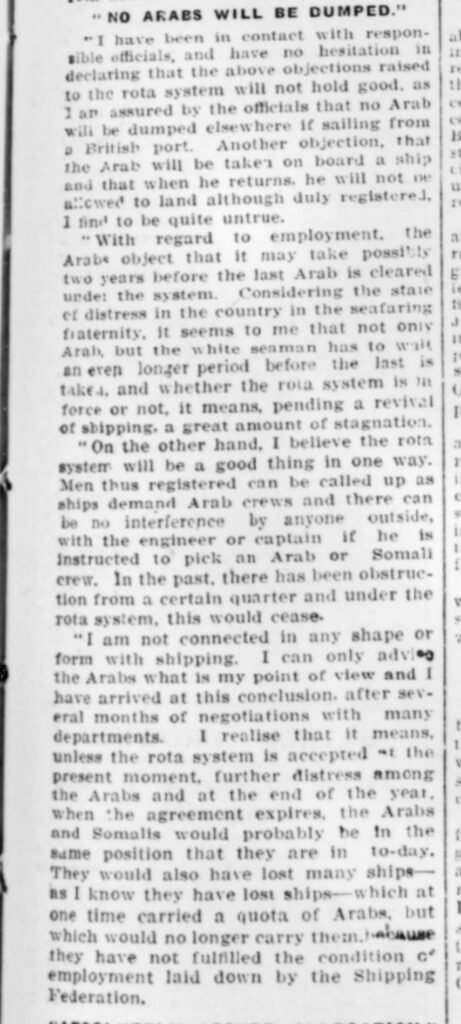

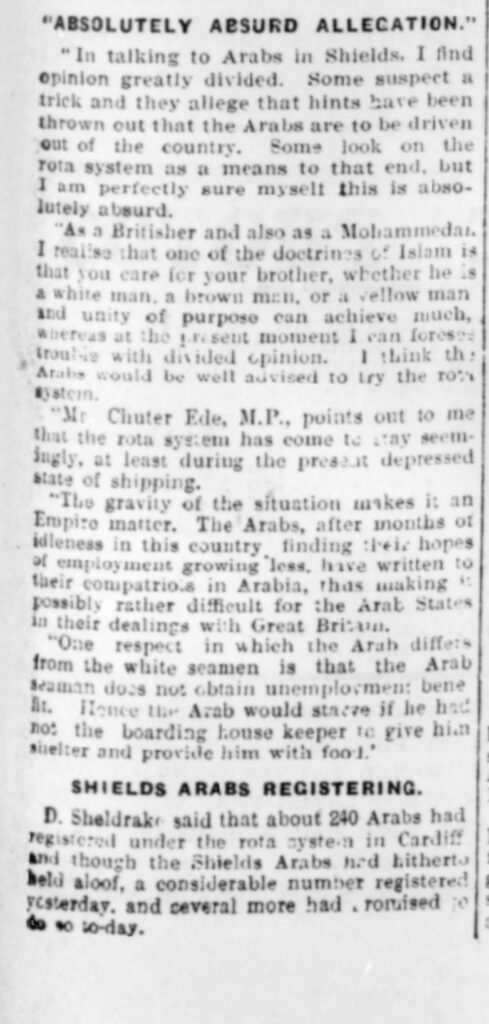

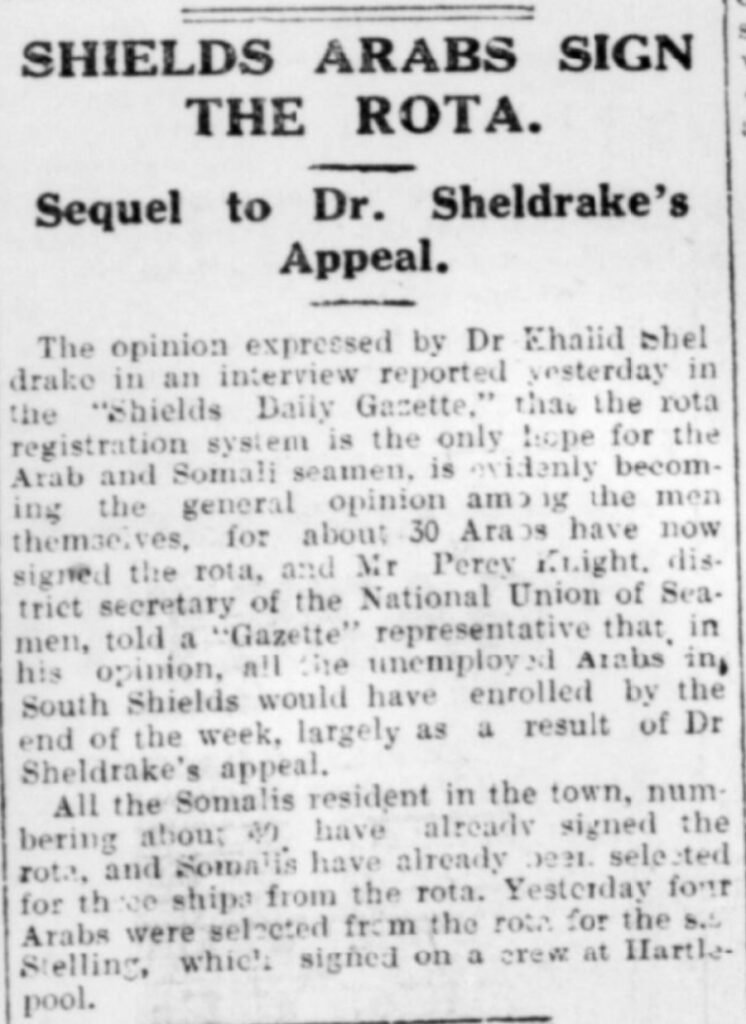

Sheldrake appeals to The arabs

Consequently, following the riots, Life President of the Western Islamic association Dr Khalid Sheldrake wrote to the Arabs of South Shields seeking to reassure them and urging them to accept the scheme for their own sake.

(c) The shields gazette 05/09/1930

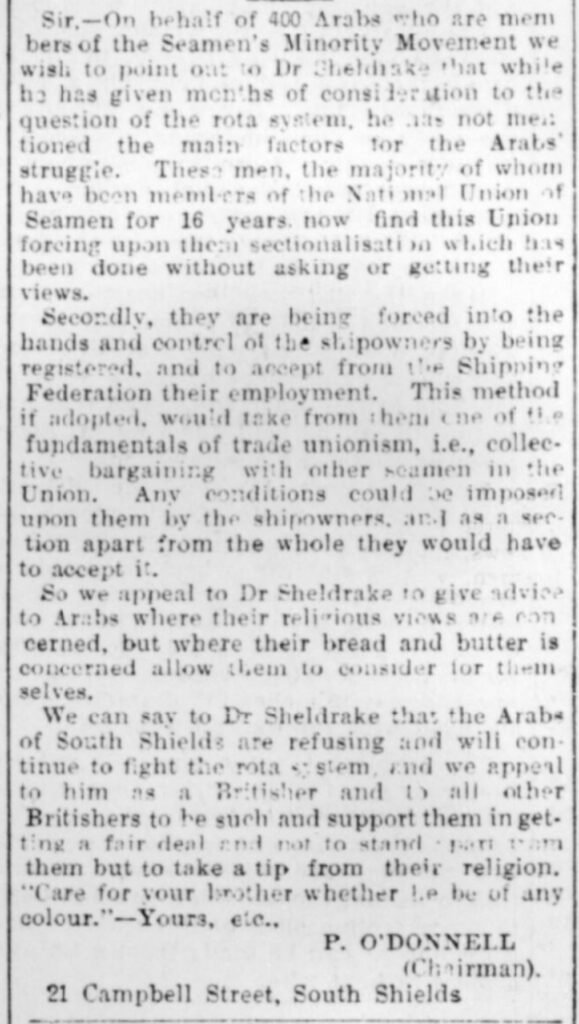

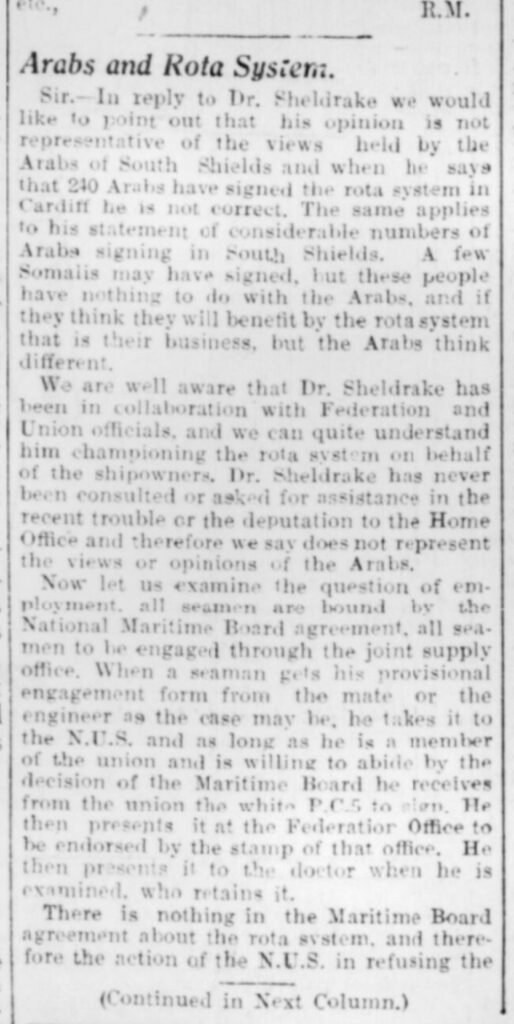

This was met with a mixed response and was certainly not appreciated by the Seamens Minority Movement.

(C) The Shields Gazette 09/09/1930

(c) The Shields Gazette 11/09/1930

After the riots there was a reluctant acceptance to the rota system as it became clear that it was not going away. The Seaman Minority Movement was no longer allowed to publicly picket and resistance decreased.

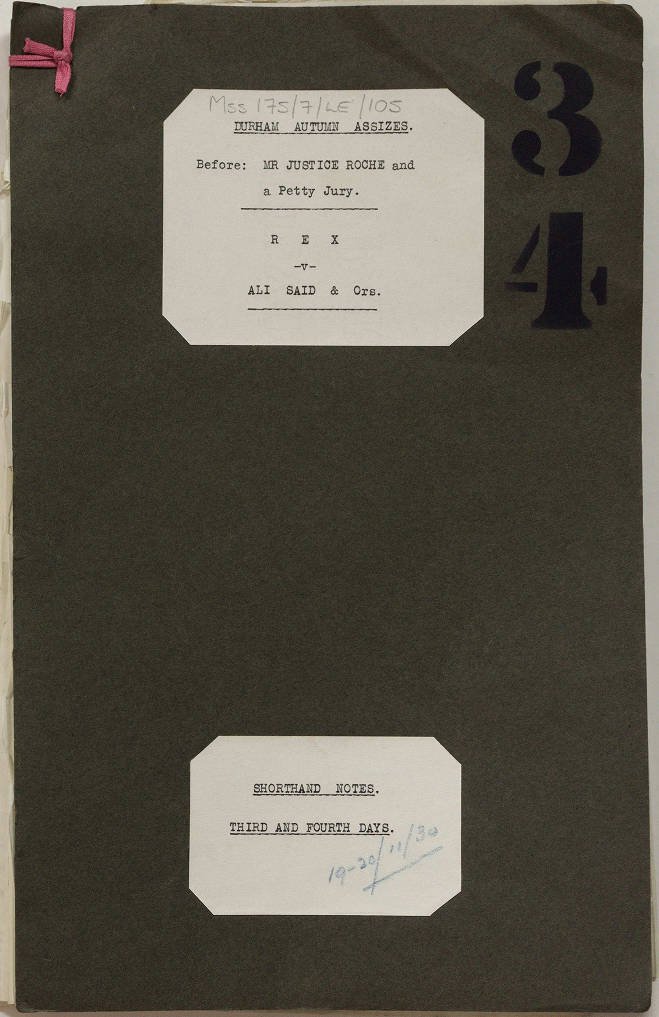

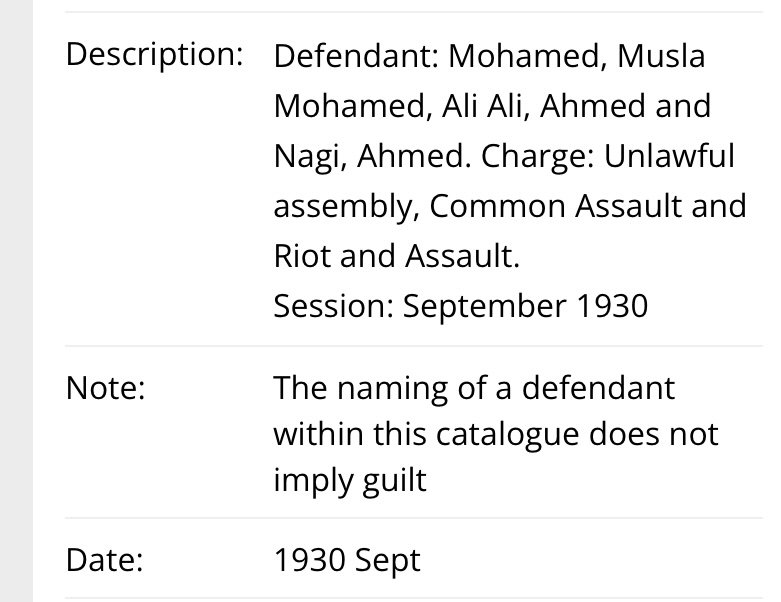

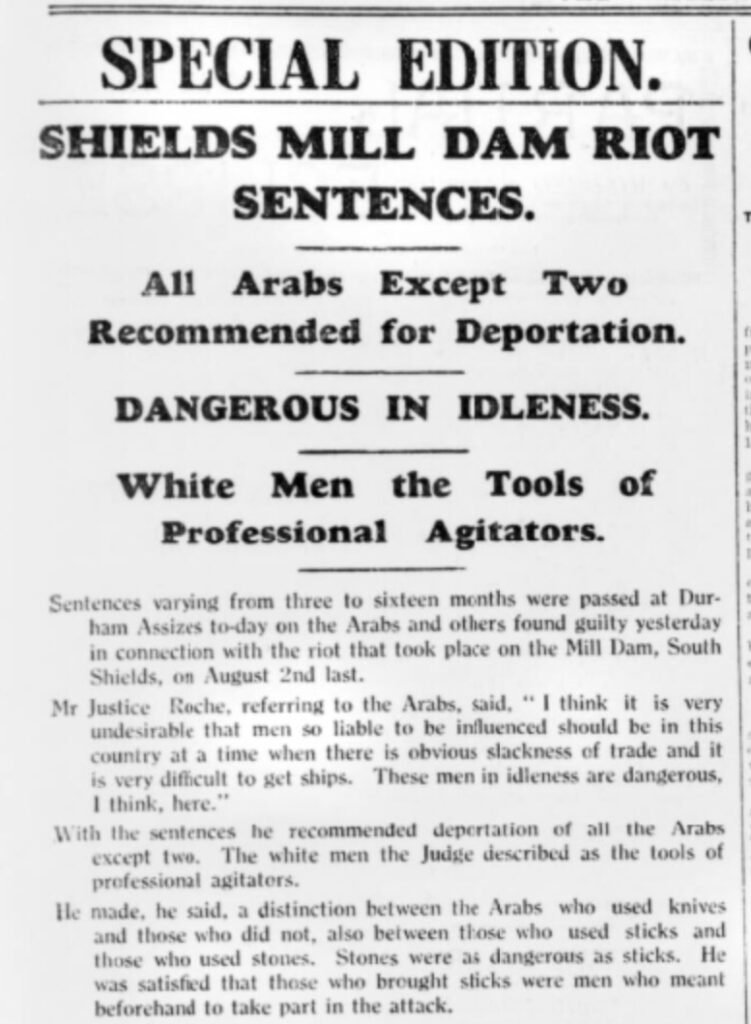

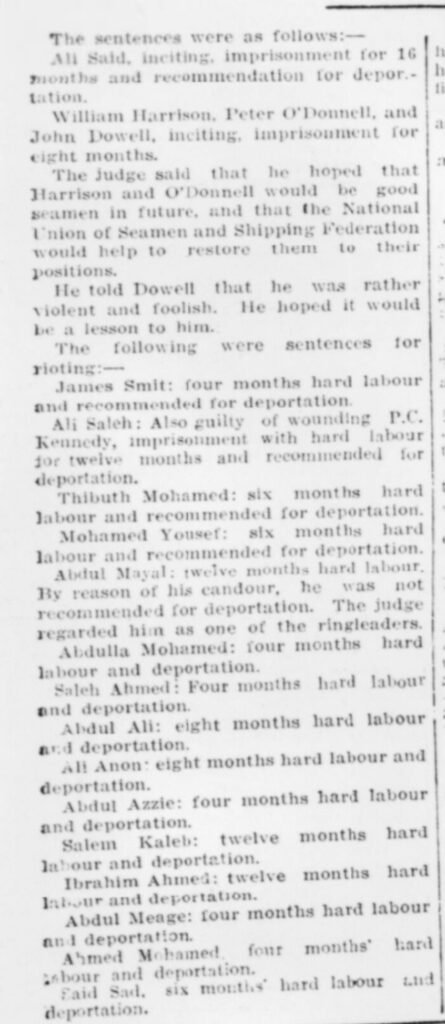

Trial – deportations

(c) South Tyneside Libraries

With thanks to South Tyneside Libraries, second last photo (c) Newcastle Chronicle

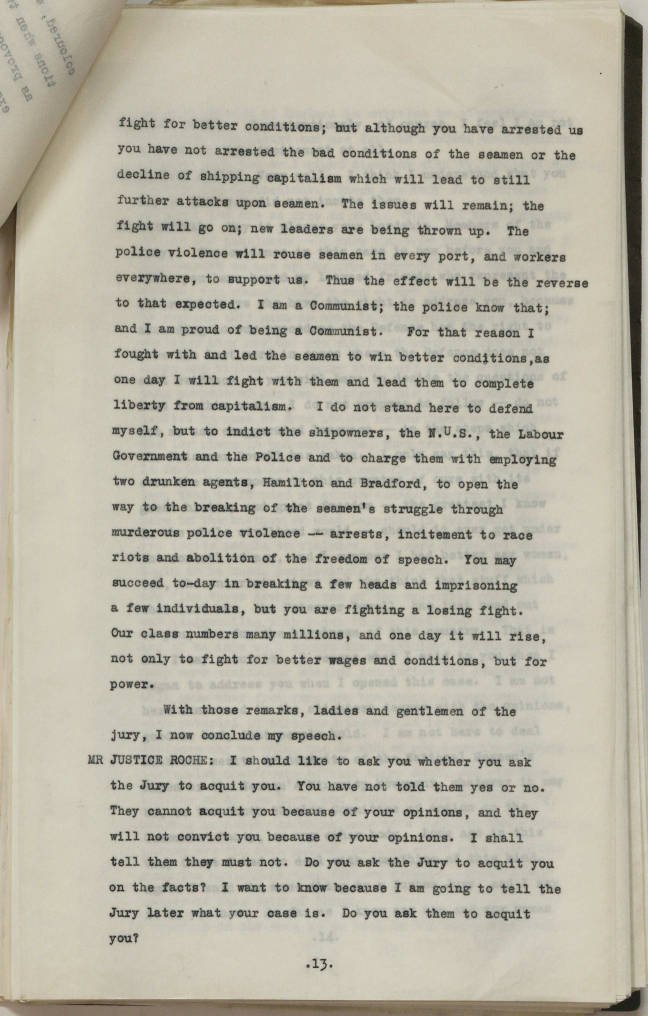

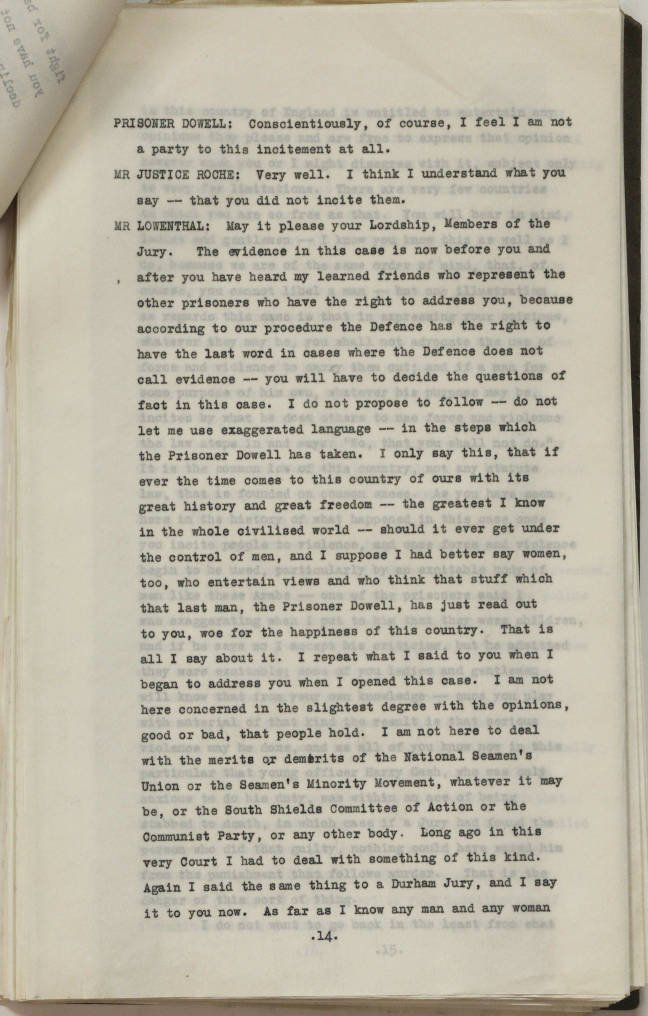

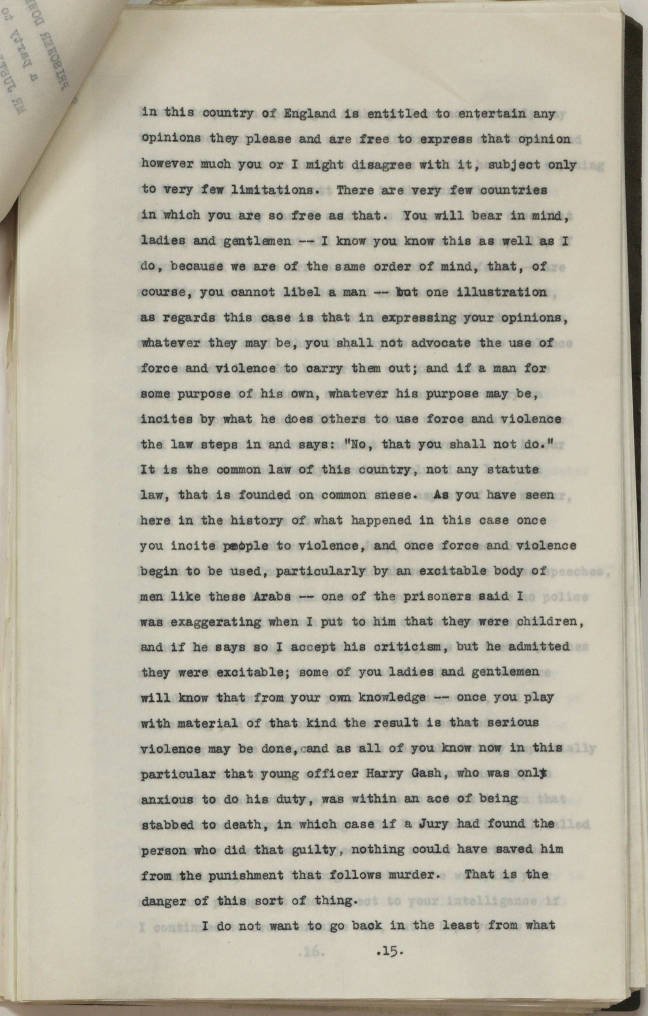

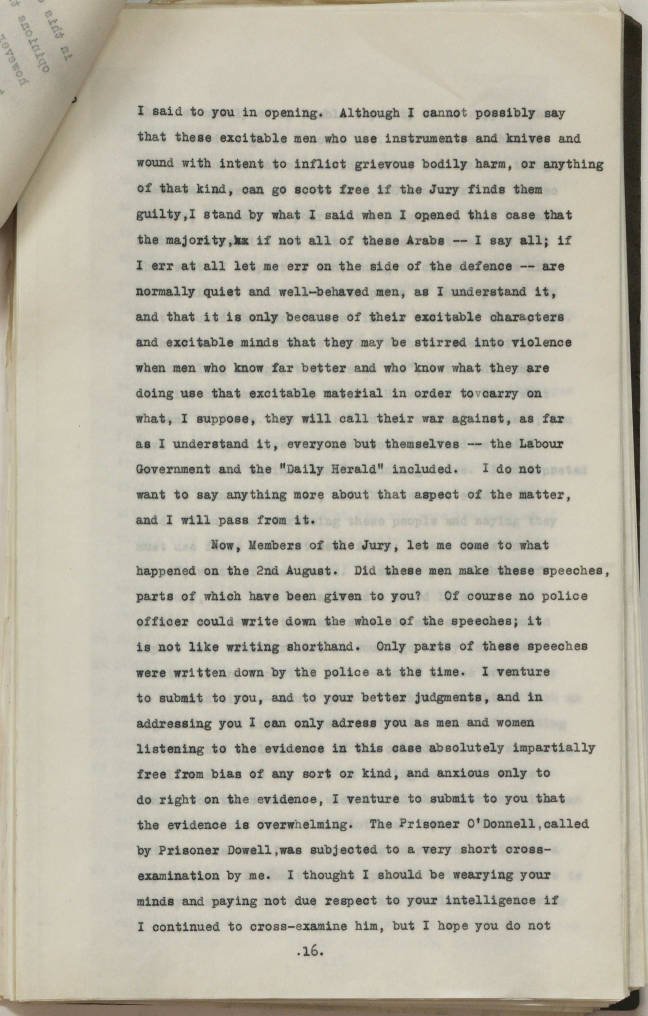

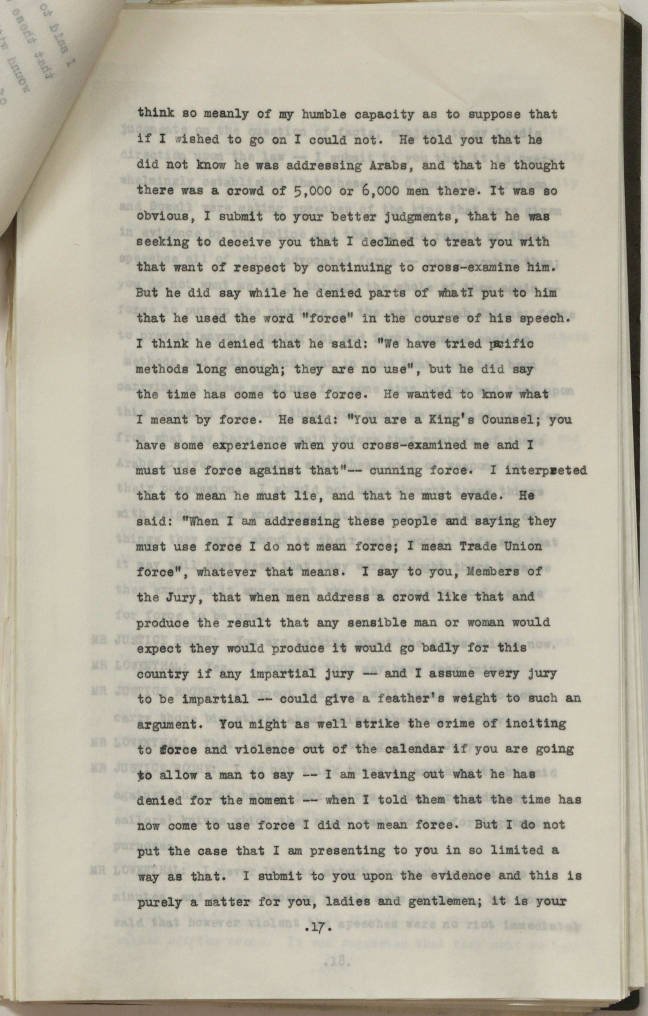

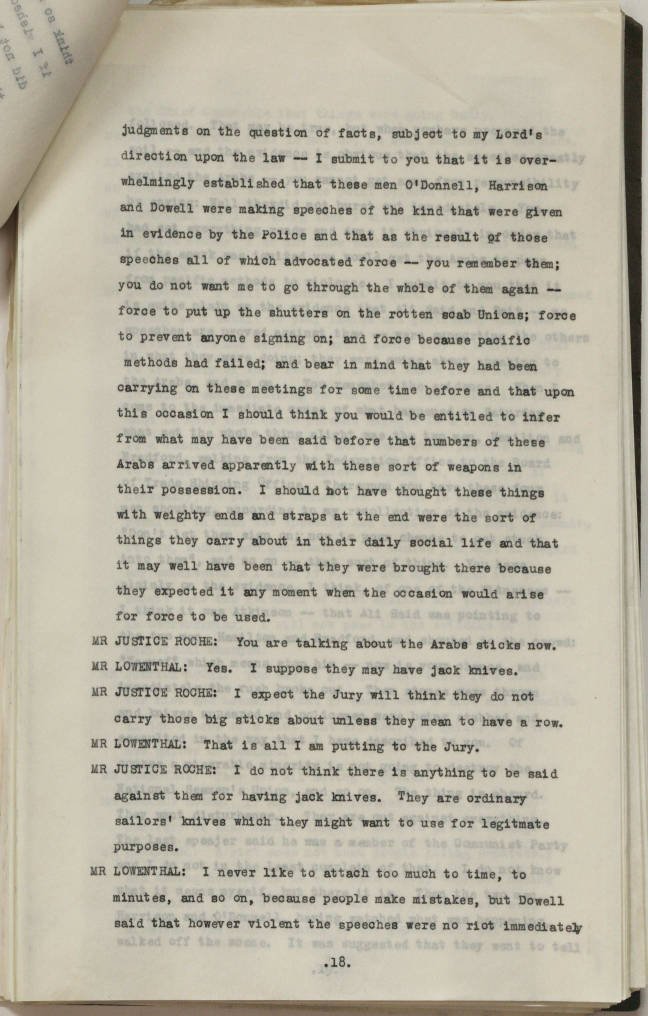

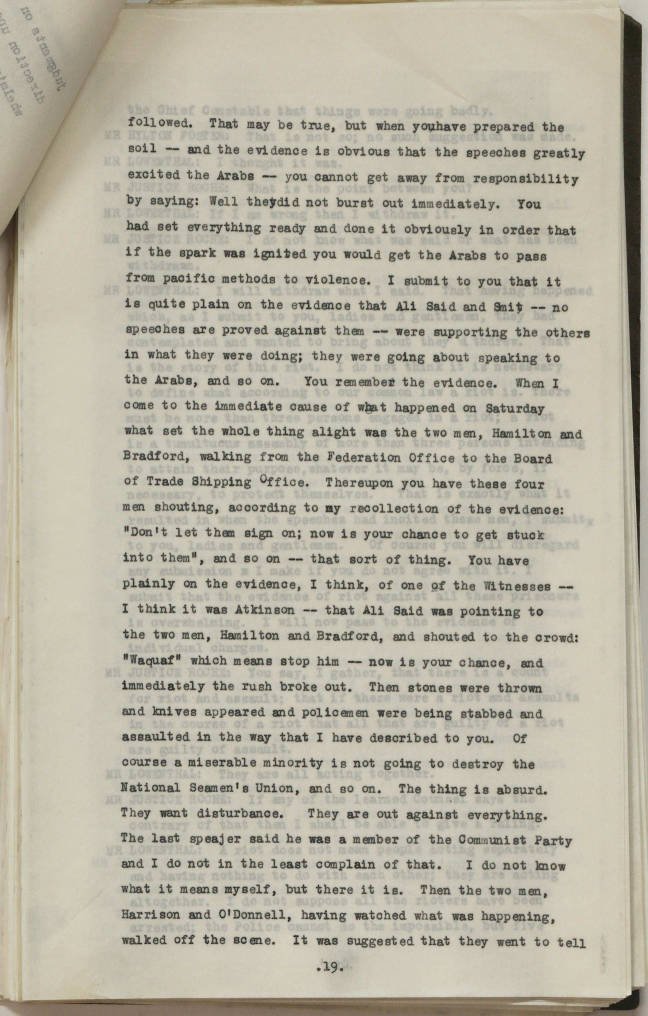

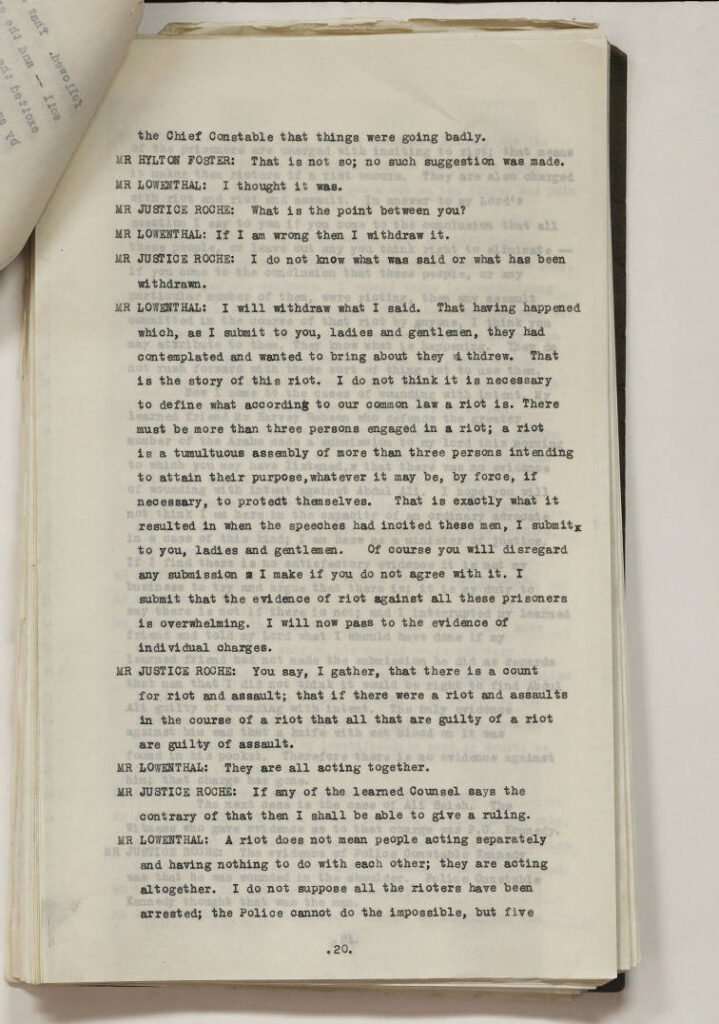

Body of the article covering the trial

(c) The Shields Gazette 18/11/1930

Photo of the archives held in Newcastle (c) Tyne and Wear Archives

names of defendants in 1930 court case held by the national archives

(c) The Shields Gazette 20/11/1930

Emily Dixon states in her article discussing race relations in South Shields that Ali Said was deported along and she notes the disparity between the punishments handed out to Arab and white people involved in the riots. Whilst it is disputable what Ali Saids role actually was without hard evidence, it is clear that his deportation was about a lot more than this isolated incident and he was a problem to the police that they wanted to deal with.

“Some fifteen to twenty Yemeni seamen were imprisoned, sentenced to hard labor, and subsequently deported. Among them was Ali Said, who had opened South Shields’ first ‘Arab Seamen’s Boarding House’ in 1909, and played no role in the fray other than to call for it to stop.”

(c) The Shields Gazette 10/09/1930

officers involved

(c) The Shields Gazette 09/06/1936

(c) The Shields Gazette 01/08/1940

Secondary Sources

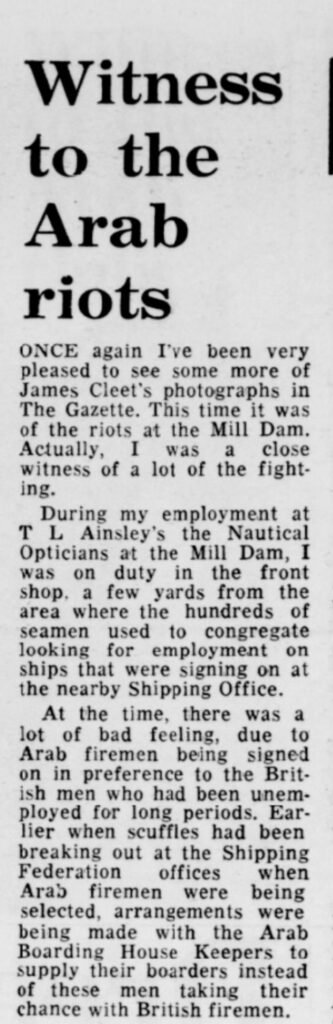

(c) The Shields Gazette 19/01/1987

(c) The Shields Gazette 19/01/1987

(c) The Shields Gazette 11/12/1995

As you can see by the photographs included, history seems to have recorded only Yemeni men:

(a) getting arrested, and

(b) in court.

These events of 1919 and 1930 are widely known as ‘Arab riots’. Naming these events in this way immediately connotes the Arabs as unruly and chaotic. A person can not help but to imagine Arabs rioting in the streets of South Shields by the name alone, without any supporting context.

Present Day – The Mill Dam is no longer used as a shipping port. The Customs House is now a much loved and popular theatre and cinema. This blue plaque, which was photographed in 2022, remains on the building to remember it’s history as the place of a Customs Port.

- Dixon, E. (2019). True North – The Delacorte Review. [online] The Delacorte Review – Real true stories (and how they happen). Available at: https://delacortereview.org/2019/02/17/true-north/ [Accessed 28 Jul. 2025]. ↩︎

- Lawless, R.I. (1995). From Taʻizz to Tyneside. p. 122 ↩︎

- Ibid., 167 ↩︎

- Anon, (2025). The Seaman. [online] Available at: https://mrc-catalogue.warwick.ac.uk/records/NUS/6/3/21 [Accessed 28 Jul. 2025].

↩︎ - Parliament.uk. (2025). COLOURED SEAMEN (REGISTRATION, BARRY). (Hansard, 30 October 1930). [online] Available at: https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1930/oct/30/coloured-seamen-registration-barry [Accessed 28 Jul. 2025].

↩︎ - Lawless, R.I. (1995). From Taʻizz to Tyneside. p. 122 ↩︎

- Dixon, E. (2019). True North – The Delacorte Review. [online] The Delacorte Review – Real true stories (and how they happen). Available at: https://delacortereview.org/2019/02/17/true-north/ [Accessed 28 Jul. 2025].

↩︎ - Lawless, R.I. (1995). From Taʻizz to Tyneside. p. 127 ↩︎

- Ibid., 137 ↩︎

- Ibid., 139 ↩︎

- Ibid., 151 ↩︎

- Ibid., 139 ↩︎

- Ibid., 117 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid., 137 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid., 152 ↩︎

- Ibid., 149 ↩︎

- Ibid., 146- ↩︎

- Ibid., 147 ↩︎

- Dixon, E. (2019). True North – The Delacorte Review. [online] The Delacorte Review – Real true stories (and how they happen). Available at: https://delacortereview.org/2019/02/17/true-north [Accessed 29 Jul. 2025].

↩︎ - Tina Gharavi, 2014. Last Of The Dictionary Men: Stories from the South Shields Yemeni Sailors. P.13-14 Edition. Gilgamesh Publishing. ↩︎